Reading: Incremental Net Cash Flows

5. Transfer Prices and Consulting Fees

Large companies with multiple divisions and/or international activities usually set transfer prices for within-firm transactions (e.g. when transferring goods from the producing to the selling division). Similarly, headquarter often charge subsidiaries consulting fees or royalties for the services that headquarter provides or the intellectual property that the subsidiaries use. With these transfer prices, consulting fees, or royalties, firms can shift profits to more tax-favorable jurisdictions.

How to handle these situations? Let us take a look:

Consulting fees and royalties

- Only apply the charges if they occur "at arm's length" and therefore reflect a market price.

- For example, if headquarters provide actual consulting services (e.g., help the subsidiary enter the market or calibrate its strategy) that would otherwise need to be sourced from professional consulting firms, we should reflect the costs of these services as a cash outflow.

- In contrast, if there are no actual services behind the service charges, these outlays should be ignored in the project valuation!

Transfer prices

- The same rule applies for transfer prices. Whenever possible, we should use actual market values instead of internally "fabricated" transfer prices.

- Again, the reality is often somewhat more complex, as the following example shows.

Example

Consider a firm with two divisions: Production and sales. You are a project manager in the sales division and your task is to determine the incremental cash flows of the following project:

- You can sell 1'000 units to a client at a price of GBP 120 each.

- To understand whether the deal is financially attractive, you consult the production division, which informs you that the internal transfer price is GBP 100 per unit.

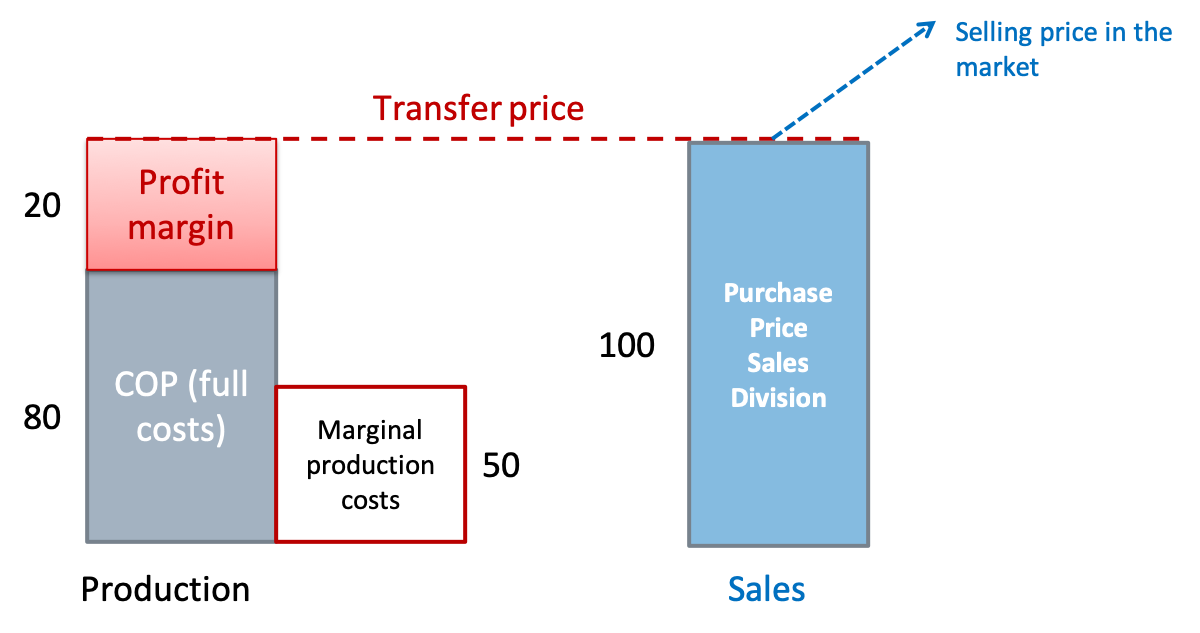

- You also obtain the information that the production division' marginal production costs are GBP 50 per unit (this is how much it actually costs them to produce an additional unit), that the full production costs are GBP 80 per unit (this includes overhead, depreciation, etc.) and that the production division's profit margin is GBP 20 per unit. The following figure summarizes the firm's cost and transfer price constellation:

Which purchase price should you now use to compute the marginal cash flows of your project? Again, it depends... While the correct answer can be virtually any number, it is very unlikely that the actual transfer price is the purchase price that you should use! To see this, let us consider a few scenarios:

Scenario (1): The units have been produced. They cannot be sold elsewhere. Without your project, they would need to be disposed of for GBP 5 per piece.

- In this case, your relevant purchase price should be GBP −5 per piece so that the incremental profit is GBP 125 per unit.

- The best alternative use of the units is to destroy them at a cost of GBP 5 per piece. Your project proposes a slightly better use. By proceeding with your project, the firm, overall, gains GBP 125 per piece.

Scenario (2): The units have not yet been produced. The production division has available capacity that cannot be used otherwise.

- In this case, the relevant purchase price should be GBP 50 per piece, i.e., the production division's actual incremental costs of production.

- If the firm proceeds with the project, it produces the units at GBP 50 and sells them for GBP 120, for an incremental profit of GBP 70 per piece.

- The actual transfer price is irrelevant, as it only allocates the incremental profit of GBP 70 between the two units. For the firm as a whole, and ignoring tax and other considerations, the incremental profit will be 70 regardless of the transfer price!

- Another way to see this is to remember the discussion in the section on synergies. If the firm sticks to a transfer price of 100, scenario (2) creates a positive synergy of 50 in the production division, i.e., the transfer price of 100 net of the marginal production costs of 50. This synergy is caused by your project, which is why you should reflect it as a cash inflow in your valuation.

Scenario (3): Capacity is limited. The units could be sold in another project for GBP 140 per piece.

- Finally, if capacity is limited, selling goods in one project could cannibalize other projects.

- According to our assumptions in scenario (3), it is not worthwhile to proceed with your project. The reason is that the units can fetch a higher price elsewhere.

- Again, the transfer price is irrelevant. What matters is the best alternative use of the goods that you can sell.

This example shows that what matters for project valuation are the firm-wide incremental cash flows. We need to know the incremental cash flows associated with the best alternative use of the resources we need for our projects. The internal transfer price will only coincidentally correspond to that incremental cash flow. Therefore, we should ignore transfer prices unless they constitute a fair market price.

It is important to note that these considerations ignore tax effects. If transfer prices can be used to shift profits from jurisdictions with high taxes to jurisdictions with low taxes, the transfer price might affect the project's incremental cash flows. In such a situation, the proposed procedure is as follows:

- First compute the project's stand-alone value as outlined above. That is, use market prices wherever possible.

- Second, compile a separate valuation of the tax effects due to transfer pricing.

- The overall value of the project then corresponds to the sum of the two valuations, i.e., the stand-alone value plus the value of the tax effects.