Reading: Financing and Experimentation

4. Value Drivers

4.1. Degree of Uncertainty

The ability to run experiments is particularly attractive when we are dealing with so-called long-shot investments, i.e., investments that offer a very high payout with very low probability. Because of the large leverage between required investment and potential payoff, the marginal value of improving the success probability is comparatively higher for such projects.

Improving the odds of long-shot investments

To see this, we can go back to our initial example, which promised to convert an investment of 12 million into 1 billion with probability 1%. If we can improve the success probability of this project by 1 percentage point, the expected value of the payoff increases by 10 million (0.01 × 1'000 = 10 million), which corresponds to 83.3% of the required investment (= 10/12). A dollar invested into an experiment to improve the success probability of such a long-shot project therefore has a potentially high return on investment.

Improving the odds of less risky investments

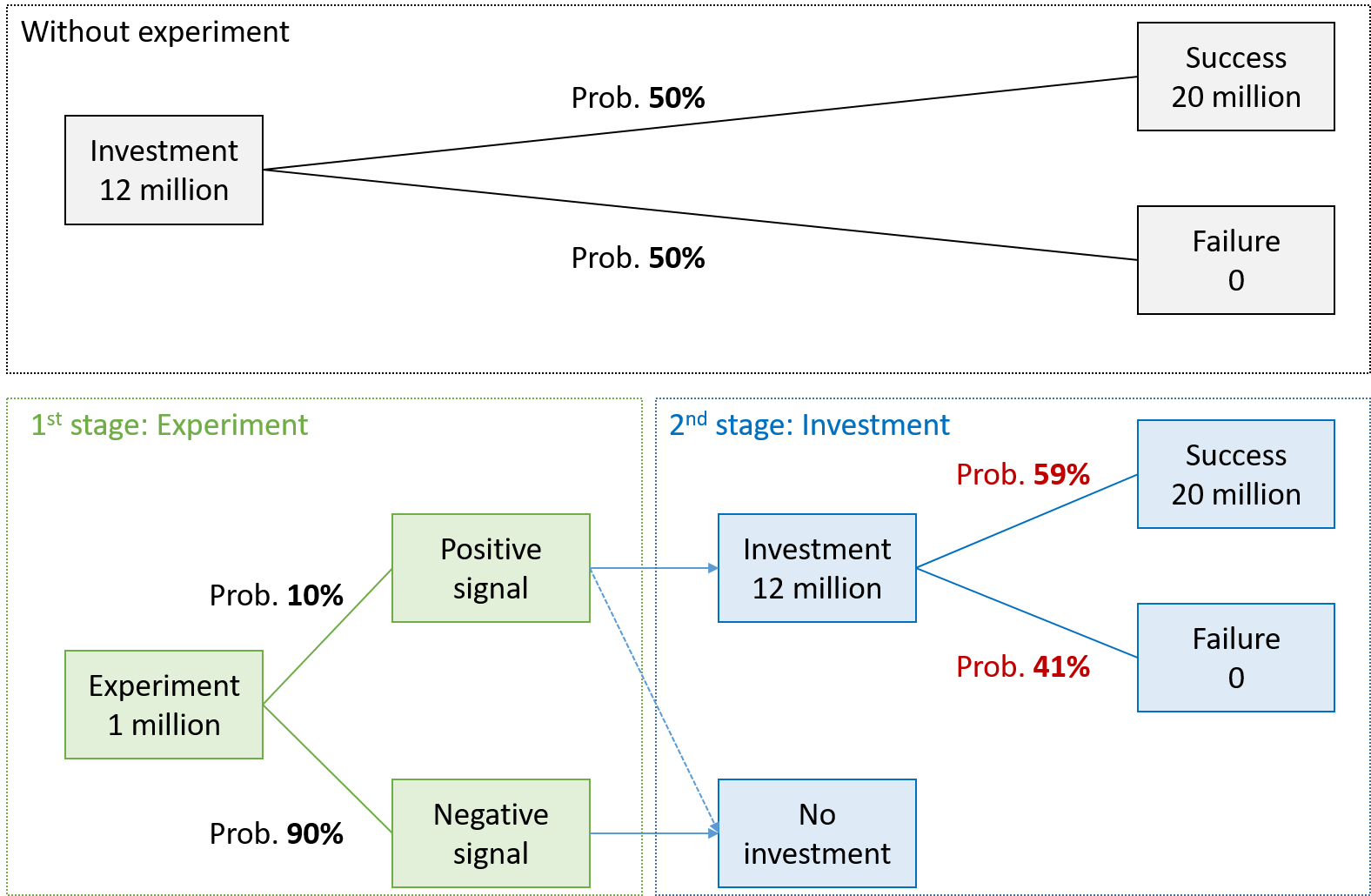

In contrast, consider the investment project summarized in the figure below:

- As in the original example, the project requires an investment of 12 million and has an expected payoff of 10 million, so that the stand-alone NPV is -2 million.

- However, there is less uncertainty associated with the future payoffs. There is a 50% success probability (instead of 1%), in which case the investment has a value of 20 million. In the alternative failure scenario (probability 50% instead of 99%), the payoff has zero value.

- As in the initial example, we can conduct an experiment for 1 million that sends a positive signal with probability 10%. If so, the success probability of the investment increases by 9 percentage points from 50% to 59% (in the original example, the success probability also improved by 9 percentage points, from 1% to 10%).

Clearly, it is not worthwhile to undertake the experiment:

- An increase in the success probability by 9 percentage points is not sufficient to turn the investment into a positive-NPV project. At 59% success probability, its NPV is -0.2 million (= -12 + 0.59×20).

- Therefore, regardless of the signal from the experiment, rational investors would not invest.

Summary

The takeaway from this simple illustration can be generalized: Experimentation is particularly valuable in situations of extreme uncertainty (long-shot investments). Very often, such investments are not feasible with full up-front investments. Experimentation, and the staged financing that comes with it, allows investors and entrepreneurs to reduce the riskiness of the project before committing the full capital.

In contrast, experimentation is often comparatively less valuable in situations with low uncertainty. There, the additional information gained from experiments is often of insufficient value to justify the costs. In such an environment, a less iterative product development strategy might be preferable.

While this conclusion sounds trivial, its implications are far reaching:

- Management philosophies such as Agility do not strictly dominate more traditional and centralized forms of management. The right model depends on the characteristics of the business or business unit.

- Areas with great uncertainty should be managed more agile, while less uncertain activities should be more centrally managed.

- This also means that more often than not, firms have to unite multiple management styles under one roof, which inevitably leads to tensions.

- The central challenge is to identify which management style is appropriate for which business activity at which stage of the lifecycle.

- As it turns out, an important step in implementing agility is to understand which areas of the business DO NOT require agility.