Reading: DCF for Startups

2. Uncertainty in the Business Model

Compared to more mature firms, startups generally face much more uncertainty about their future business model. They might have a fascinating technological idea, possibly (hopefully) with a proof of concept and some running test applications, as well as a clear roadmap towards how to enhance that technology. They are usually also convinced that there is a tremendous market potential for their invention, without any serious competitors on the radar screen.

For many entrepreneurs, it is comparatively easy to imagine sales in the millions. How to sell the first unit, however, is often a much harder question to answer. In other words, having a great idea and monetizing that idea are often two completely different challenges. In fact, many startups with great business ideas fail not because there is no demand for their product but because they can’t bring that product to the market.

Now finance does not tell an entrepreneur how to monetize her business idea. But it provides the necessary perspective. In particular, the financial plan forces her to systematically think through the business case and model the future (financial) evolution of the firm with a complete chain of arguments and key assumptions. This often makes it easier for the analyst or investor to identify missing steps and validate key assumptions.

The above arguments in favor of financial planning are very general and obviously also apply to mature firms. But they are particularly relevant for startups because these firms often lack specific experience.

Because startups have lots of uncertainty in their business model, a single financial plan is generally not sufficient. A newly launched fashion label, for example, might consider various alternatives to distribute its clothes (e.g., online, with its own stores, in cooperation with shopping centers, or through a joint venture with an established player). It might also consider various pricing strategies (from luxury to mass-market). Fur such a firm, it makes sense to model the most important strategic alternatives in separate financial plans. This provides the management and potential investors with key insights about the viability and attractiveness of the various strategic options under considerations. It also helps them identify the key value drivers for each alternative and define early warning signals.

For the actual valuation of the company, we can then either value the various strategic alternatives separately (that is, simulate alternative possible paths of the company and determine the respective values) or generate a financial plan that reports the (weighted) average of the various strategic alternatives and then conducts a “single” valuation of the firm.

The following example illustrates these considerations:

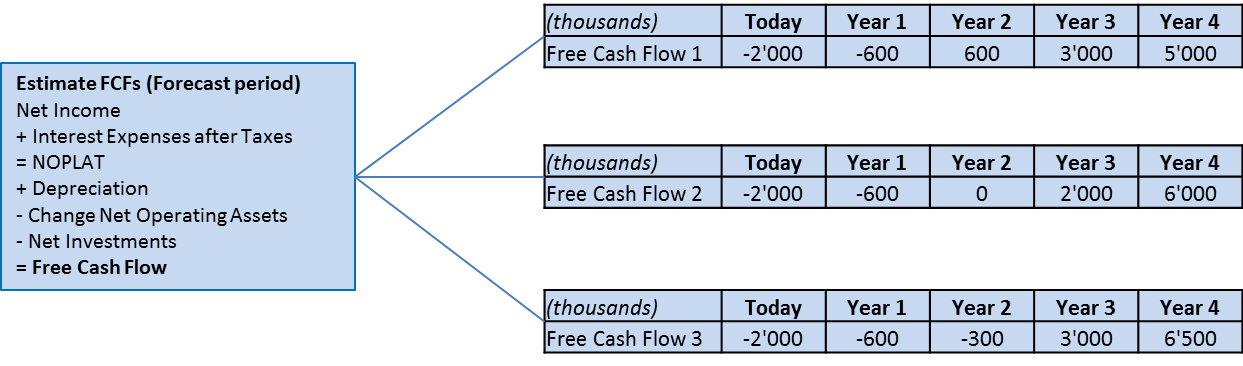

Suppose a firm considers three strategic alternatives (1, 2, and 3) to launch its products. For each of these alternatives, it compiles a detailed financial plan. Let's assume that the numbers in the following figure summarize the free cash flows that follow from the three financial plans:

Each scenario has the same expected cash flows over the next two periods (i.e., product development is the same regardless of distribution strategy). Only afterwards, the three alternative differ in terms of cash flows. Also suppose that, as of today, the management assigns a probability of 30% to Alternative 1, a probability of 30% to Alternative 2, and a probability of 40% to Alternative 3. Finally, for simplicity, let us assume that all three alternatives command a risk-adjusted return of 10% (more on this later).

With this information, we could then look at the value implications of the three scenarios. If we stick to the DCF model, we could first value the three alternatives and then compute a weighted average of the resulting valuations:

DCF-Value of Alternative 1 = \( -2'000 + \frac{-600}{1.1} + ... + \frac{5'000}{1.1^4} \) = 3'619

DCF-Value of Alternative 2 = \( -2'000 + \frac{-600}{1.1} + ... + \frac{6'000}{1.1^4} \) = 3'055

DCF-Value of Alternative 3 = \( -2'000 + \frac{-600}{1.1} + ... + \frac{6'500}{1.1^4} \) = 3'900

Using the probabilities from above, we can now estimate the DCF-Value of the firm, given the three strategic alternatives:

DCF-Value of Firm = \( 0.3 \times 3'619 + 0.3 \times 3'055 + 0.4 \times 3'900 \) = 3'562.

Consequently, our assumptions imply a current value of the firm of roughly 3.5 million. The valuations also reveal that Alternative 3 is the most promising stratigic alternative. Therefore, an exercise like this also shows the management on which strategy it should focus and where it should work hard to improve the odds of success.

Additional important information can be gained when we consolidate the various cash flow scenarios over the anticipated life of the firm. Remember that the first two cash flows are identical across alternatives, namely -2'000 and -600, respectively. For the remaining cash flows, we can compute their probability-weighted average. In the case of year 2, for example, the expected free cash flow at the firm level is:

Expected FCF Year 2 = \( 0.3 \times 600 + 0.3 \times 0 + 0.4 \times (-300) \) = 60.

The following table summarizes the results also for the remaining years:

|

(thousands) |

Today |

Year 1 |

Year 2 |

Year 3 |

Year 4 |

|

Expected Free Cash Flow |

-2'000 |

-600 |

60 |

2'700 |

5'900 |

With this information, we could now also estimate the current value of the firm, which (still) is:

DCF-Value of Firm = \( -2'000 + \frac{-600}{1.1} + ... + \frac{5'900}{1.1^4} \) = 3'562.

More importantly, the above table shows us the firm's expected cash flow profile based on the currently available information. For example, it shows us that the firm is expected to generate positive free cash flows after two years. Put differently, the firm's operating business is expected to generate sufficiently positive cash flows by then to support the planned investments.

The recommendations that follow from these considerations are simple:

- The management should think about its most promising strategic alternatives going forward. In most cases, this involves a significant effort in terms of market research and some important considerations about pricing and distribution.

- The management should then model the financial implications of these alternatives. This forces the managers to systematically think trough the business case and identify the key value drivers (and success risks).

- The resulting financial plans can be assessed separately. This provides the management (and potential investors) with important information about the financial attractiveness of the strategic choices. It also makes it easier for the management to set the right priorities.

- Finally, the financial implications of the various strategic alternatives should be consolidated into one financial plan. With this consolidated financial plan, the relevant stakeholders can identify the financial profile of the firm and derive important information such as by when the business is expected to be self-sustainable and when it is expected to break even.

Now all of this sounds fairly simple on paper. In reality it is obviously not that simple. Especially in a very dynamic environent, the half life of a financial plan could be very short. It is therefore important for entrepreneurs to find the right balance between trying to model the future and actually creating that future. Experience shows that a rough understanding of the main financial mechanics of a business case (i.e., the 5-or-so most important value drivers and their interplay) can often be more useful than a very detailed financial model. Experience also shows, however, that firms that neglect the potential financial implications of their business ideas usually do not make it far.