Reading: Division of Returns

Reading assignment for the section "Division of Financial Returns"

3. Liquidation Preference

3.1. Straight Equity

Let us start with a deal structure with common equity. First, it is important to note that, in principle, the investment makes sense for the VC as well. According to his assessment:

- The post-money valuation of the firm is 15 million

- The required capital is 10 million.

Hence, the VC will be willing to invest as long as he gets 66.7% or more of the firm's common equity:

Required ownership stakeVC = \( \frac{Investment}{\text{Post-money valuation}_{VC}} = \frac{10}{15} \) = 66.7%.

Put differently, a 66.7% ownership stake in the firm's common equity has a value of 10 million today, according to the VC. So a deal with common equity would, in principle, be possible. However, giving away 66.7% of the firm's equity might not be the preferred outcome for the entrepreneur:

- She would lose control over the firm and become a minority shareholder. This, in turn, might not be in the best interest of the VC as well, as it would probably affect the entrepreneur's commitment to the firm.

- According to the entrepreneur's own valuation (post-money value of 30 million), giving away 66.7% of the equity implies that the VC receives 20 million worth of shares in exchange for a capital investment of 10 million. To her, a fair deal would be to offer only 33.3% of common equity so that the VC covers his cost of capital.

So she will most likely not accept the deal.

Towards a Better Deal Proposal

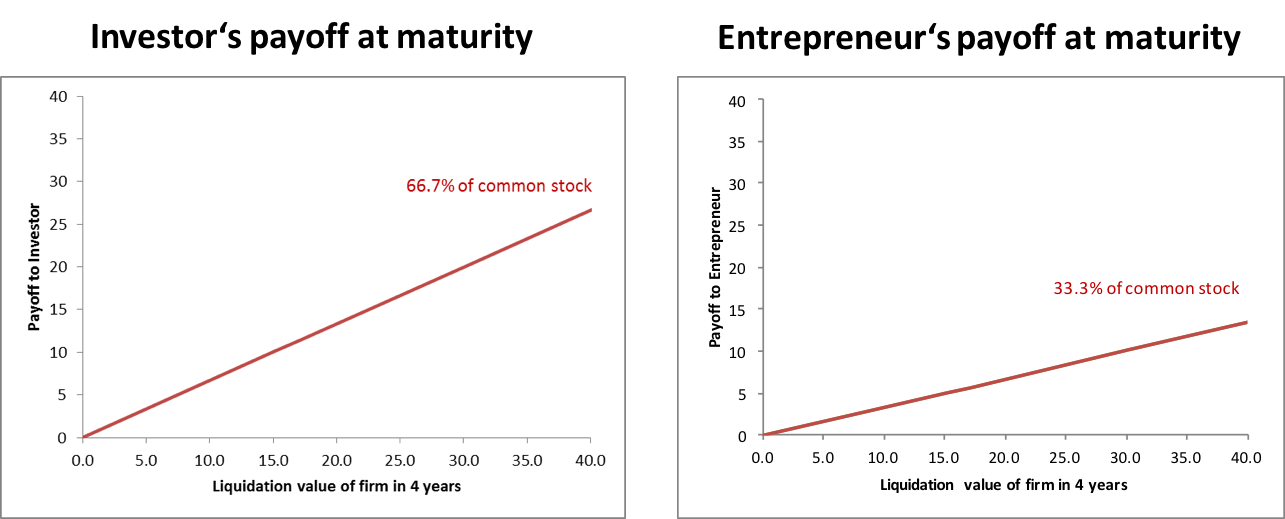

The question is whether we can we come up with a better deal proposal. To better understand the basic problem that underlies the deal with common equity, let us take a step back. The following graph summarizes the payoffs to the VC (left) and the entrepreneur (right) at maturity in 4 years, according to the initial deal idea of the VC: 66.7% of common equity to the VC and 33% of common equity to the entrepreneur.

For example, if the liquidation value of the firm is 30 million in 4 years, the payoff to the investor is 20 million (graph to the left) and the remaining 10 million go to the entrepreneur (graph to the right).

The graphs show that with a common equity deal, the liquidation value is always split proportionally between the investor and the entrepreneur: Two thirds go to the investor, one third goes to the entrepreneur. These proportions are the same, regardless of the future liquidation value of the firm.

Now why could this be suboptimal?

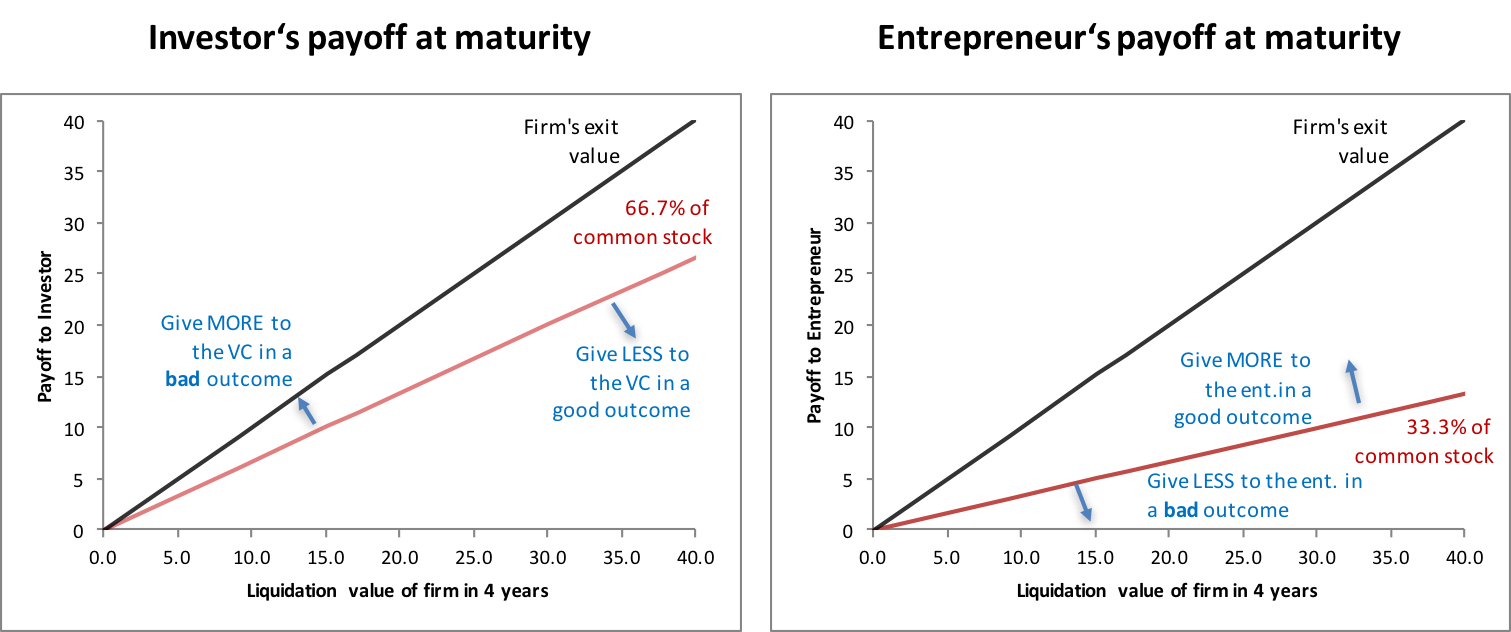

- Remember that the entrepreneur is more optimistic about the venture than the VC. This means that a good outcome is comparatively more likely according to the entrepreneur's view than according to the VC's view. In contrast, the probability attached to a bad outcome is comparatively higher for the VC than for the entrepreneur.

- This also implies that a dollar of exit value in the bad outcome is valued comparatively higher by the VC whereas a dollar of exit value in the good outcome is valued comparatively higher by the entrepreneur.

- Therefore, it could make sense to allocate the VC a higher proportion of the exit value in a "bad" outcome whereas the entrepreneur should get a higher proportion of the exit value in a "good" outcome. Thereby, we should be able to increase the (subjective) valuation of the deal by the two parties.

The following graph illustrates the adjustments we could make to the payoff scheme to incorporate the different assessments of the outcome probabilities by the investor and the entrepreneur:

Such redistributions of exit payoffs can be achieved by issuing preferred stock to the VC. This is what the next section shows.