Reading: Division of Returns

Reading assignment for the section "Division of Financial Returns"

3. Liquidation Preference

3.2. Straight Preferred

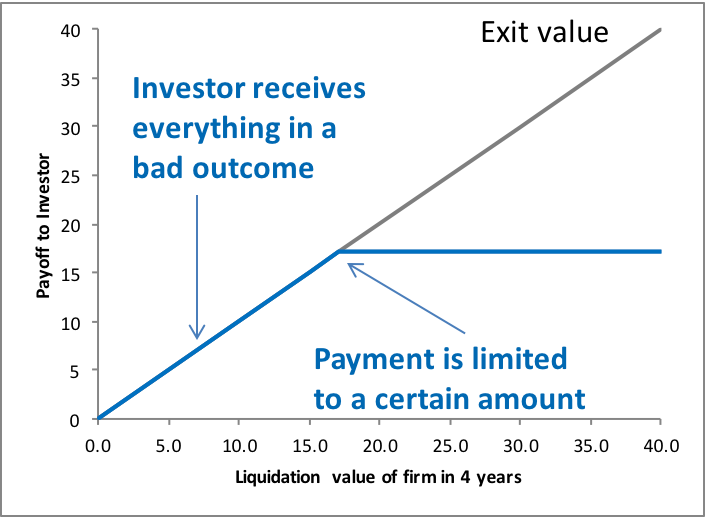

In the extreme, the adjustments discussed before imply that the VC gets the firm's full liquidation value in a bad outcome. In exchange, once his claim is covered, the remaining liquidation value goes to the entrepreneur. The following graph shows the payoff at maturity of such a financing structure from the point of view of the investor (blue line). The grey line shows the firm's total exit value.

This is the payoff structure of Straight Preferred Common Stock (also called Non-Participating Common Stock, since the investor does not participate in the upside of the firm). In a typical term sheet, financing with straight preferred common stock would be defined as follows:

In the event of any liquidation, dissolution or winding up of the Company, the proceeds shall be paid as follows:

First pay [X] times the Original Purchase Price plus accrued dividends on each share of Series A Preferred. The balance of any proceeds shall be distributed pro rata to holders of Common Stock.

The factor "X" in the above formulation (together with any accrued dividends) determines the investor's liquidation preference. Historically, most deals set the liquidation value equal to the original purchase price (plus dividends) and therefore set "X" was equal to 1. More recently, an increasing number of deals has used multiples of 2 or 3. Consequently, these more recent deal structures move the kink in the payoff to the investor further to the right. For example, with a 2x liquidation preference, the VC first gets twice his invested capital (plus dividends) before the entrepreneur participates in the proceeds of the venture.

Example

For our (stylized) example, let us assume the following financing structure with Preferred Stock:

- Dividend terms: The Series A Preferred will carry an annual 5.25% cumulative dividend, payable upon a liquidation or redemption.

- Liquidation preference: First pay 1.5 times the Original Purchase Price plus accrued dividends on each share of Series A Preferred...

With his investment of 10 million, the VC's total liquidation preference at maturity in 4 years will therefore amount to 17.1 million:

- Cumulative dividends: 4 times 5.25% on 10 million = 2.1 million

- Liquidation preference: 1.5 times the original purchase price of 10 million = 15.0 million.

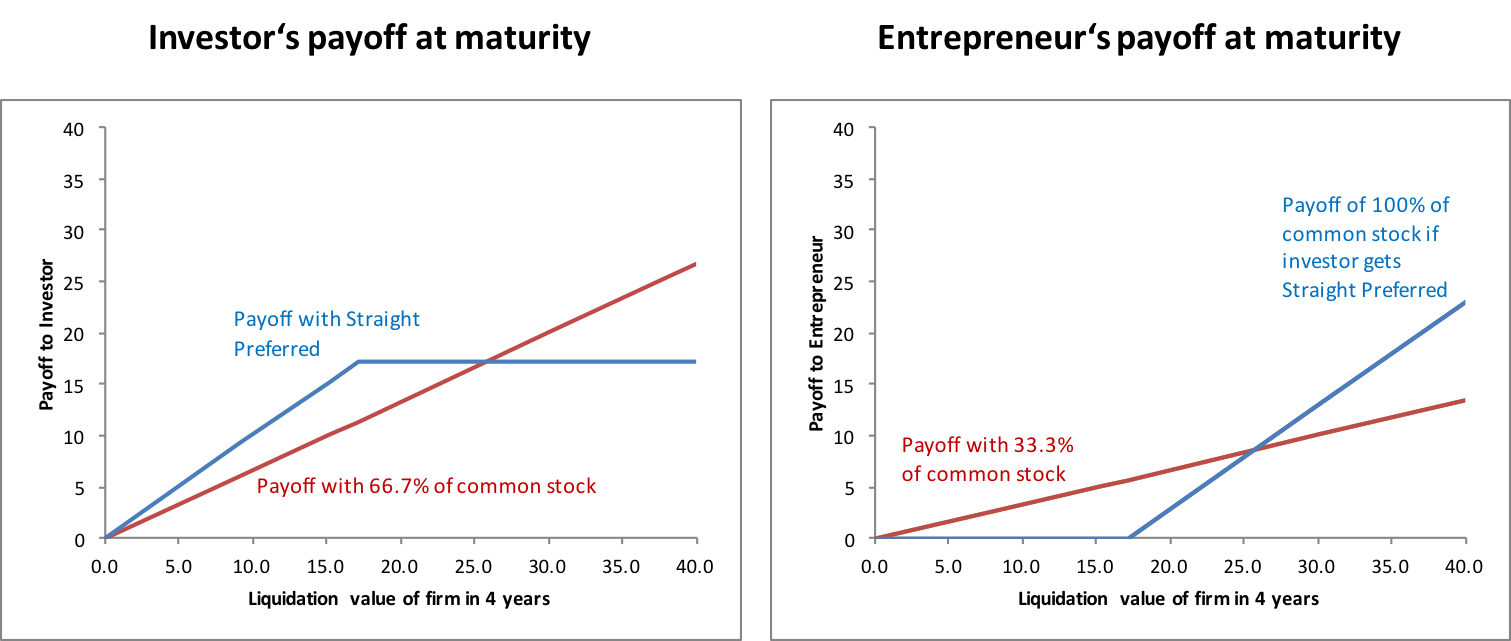

Consequently, the "kink" in the above payoff scheme is fixed at 17.1 million. For the entrepreneur, this implies that she will only participate in the liquidation proceeds if the liquidation value exceeds 17.1 million. The following graph summarizes the payoff schemes of this financing alternative to the investor (left graph) and the entrepreneur (right graph).

For example, at a liquidation value of 15 million in 4 years, the whole proceeds go to the investor (left graph) and the entrepreneur receives nothing. At a liquidation value of 25 million, the investor receives his maximal payoff of 17.1 million and the difference, 7.9 million, goes to the entrepreneur.

With such a deal structure, the investor gives up some of the upside potential (the area between the red line and the blue line to the very right of the graph) in exchange for a better protection against the downside (the area between the blue line and the red line to the left of the graph). In contrast, the entrepreneur loses the full downside protection in exchange for a greater upside participation.

Discussion

In the following course section "Valuing Financing Alternatives" we will see how to value such deal structure. For the moment, let us focus on a more qualitative interpretation of the outcome. What are the advantages of a deal structure with Non-Participating Preferred Stock?

- The new financing structure generates a high-powered incentive for the entrepreneur to work hard. If she fails to reach a liquidation value of 17.1 million, she risks losing everything.

- The entrepreneur can keep the control over the firm (if things go well).

- The VC receives liquidation preference. Therefore, his potential concerns about "take the money and run" are mitigated.

- If the entrepreneur is more optimistic than the VC, such a deal structure will generally have a higher (subjective) value for the two parties than a deal structure with common equity (we will show this in the section Valuing Financing Alternatives).

- Screening and filtering: The entrepreneur will only accept such a deal structure if she is truly optimistic (as opposed to pretending to be optimistic to get a better deal). Therefore, if the entrepreneur accepts the deal, the VC learns that she is indeed optimistic. In contrast, a refusal of the deal could be a signal that the entrepreneur is actually not as optimistic as she claims to be. Therefore, the financing structure is a sort of "truth serum" that the VC can apply to the entrepreneur.

Are there any potential disadvantages of the deal structure?

- Obviously, some of the points above could also be interpreted in a less positive way (e.g., that the entrepreneur loses everything if things do not go well).

- More importantly, the VC might have concerns with the deal structure. With Non-Participating Preferred, he does not participate in the upside if things go really well! Suppose the firm reaches an exit value of 100 million. All the VC gets is 17.1 million and the rest (82.9 million go to the entrepreneur). Under the original financing policy with common equity, the VC would receive 66.7 million and the entrepreneur only 33.3 million in this hypothetical scenario. To avoid this, the VC will generally ask for some participation in the upside.

The following sections will illustrate how the VC can participate in the upside while maintaining some downside protection. Before we discuss these deal structures, let us quickly look at liquidation preference in the case when a firm has multiple series of preferred securities outstanding.

Liquidation Preference with Multiple Series of Preferred

In later rounds of financing, firms could have multiple series of preferred securities with a liquidation preference outstanding (e.g., Series A and Series B). The question then is who gets the liquidation preference first? Put differently, what are the seniority structures among the different issues of preferred?

The following seniority structures are common:

- Standard Seniority: Liquidation preference is paid from the last to the earliest round.

- With "standard seniority," the liquidation preferences of later rounds (e.g., Series B) are senior to those of earlier earlier rounds (e.g., Series A).

- For example, if the liquidation preferences of Series A and B are 5 and 10 million, respectively, and the company sells for 12 million, Series B investors will receive the full exit proceeds of 10 million, Series B investors will receive the remaining 2 million, and common stockholders will receive nothing.

- Most startup companies have this standard seniority. The reason is very simple. Because fundraising is a tough challenge for most companies, early stage investors depend on later stage investors to provide the necessary funds for surviving. So later stage investors have a strong negotiation position, which they use to extract more favorable terms.

- Pari Passu: Under this structure, preferred shareholders across all stages share the same seniority. In the event that the liquidation proceeds are insufficient to cover all investors, the proceeds are shares pro rata to capital committed.

- For example, if the capital committed of Series A and Series B is 5 and 10 million, respectively, and the company sells for 12 million, Series A investors will receive 4 million and Series B investors will receive 8 million.

- The pari passu structure is more common among companies with a strong negotiation power towards later stage investors. Those could be "unicorn companies" (i.e., startups valued at over $1 billion) or companies with prominent founders and/or prominent early investors. These companies and early investors would simply not agree to a subsequent round of financing with seniority, and they can often choose from a large number of interested VCs.

- Tiered: In rarer instances, investors from different rounds of financing can be grouped into tiers of seniority level. With this structure, there is "Standard Seniority" between tiers and "Pari Passu Seniority" within tiers.

- A prominent example of such a structure is Elon Musk's SpaceX. The company has raised capital in 7 rounds of financing (A to G). Investors in the various rounds are grouped into 3 tiers:

- Highest seniority: Series G and E

- Middle seniority: Series D

- Lowest seniority: Series A to C.

- A prominent example of such a structure is Elon Musk's SpaceX. The company has raised capital in 7 rounds of financing (A to G). Investors in the various rounds are grouped into 3 tiers:

Straight Preferred vs. Straight Debt

When we take a careful look at the payoff chart of the straight preferred above, we see that another security factually has the same payoffs: Straight debt (e.g., a bank loan).

- Debtholders have a senior (but contractually limited) claim against the company.

- As long as the liquidation proceeds fall short of that claim, the full proceeds are allocated to the debtholders and the shareholder walk away empty-handed.

- In contrast, once the claims of the debtholders have been fullfilled, they do not participate further and all the additional proceeds go to the shareholders.

The key difference is that preferred stock is part of the firm's equity whereas debt is part of the liabilities. Simply put, debt represents a contractual claim on regular interest and notional payments and failure to meet these obligations leads to default. Debtholders, therefore, have a very effective cut-through right on the firm and its assets. These rights are much less pronounced in the case of preferred stock. For a detailed discussion of the differences between debt and equity, please refer to the course section that deals with the capital structure basics.