Reading: Understanding and Valuing Debt and Equity

3. Incentive Implications

3.1. Asset Substitution Problem

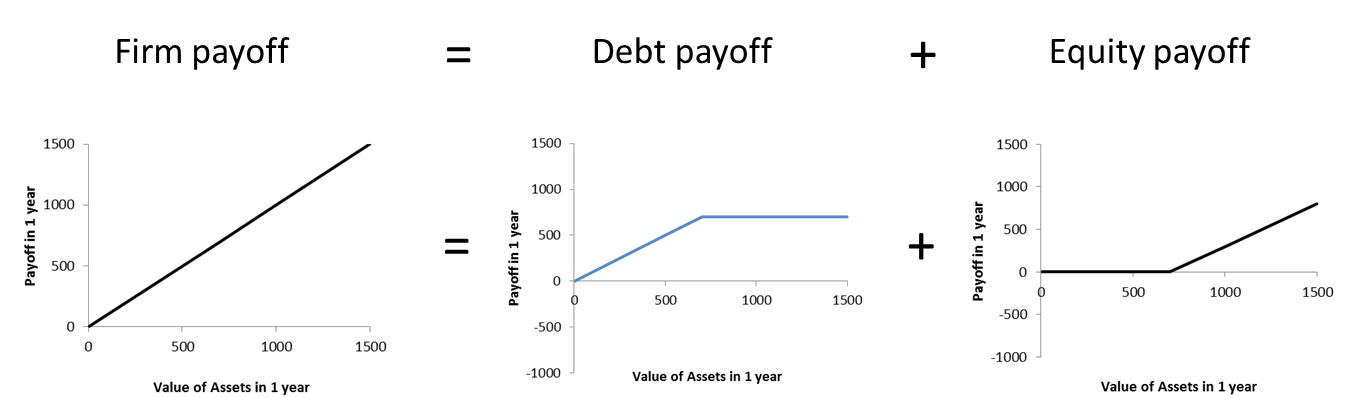

Let's start by looking at how debt financing shapes the risk preferences of the involved parties. Looking at the respective payoff charts: Who has a stronger preference for risk? The debtholders or the equityholder?

To illustrate, let us assume that the current value of the firm is 700 and therefore just equal to the claim of the debtholders.

- What would debtholders like to do?

- What are the preferences of the shareholders?

Clearly, debtholders do not like risk. The reason is very simple:

- At a value of 700, they receive their full compensation.

- Taking on risk means that the value can grow larger than 700---but it also means that it can drop below 700.

- If the value grows larger than 700, the full difference goes to the shareholders. Nothing changes for the debtholders.

- In contrast, if the value drops below 700, the full value decline goes at the expense of the debtholders. From the point of view of the shareholders, it is factually irrelevant whether the ultimate firm value is 0 or 700 or somewhere inbetween: As long as it does not exceed 700, they lose everything.

- Technically speaking, the claim of the debtholders is concave. Increasing the risk of the firm reduces the expected value of the debt claim.

- It would therefore be in the best interest of the debtholders to completely eliminate all risk.

For the shareholders, the situation is the opposite. Debt financing increases their preference for risk!

- At a firm value of 700, they experience a total loss.

- Taking on more risk increases the shareholders' upside potential without affecting their downside (they lose everything anyways if they do not act)!

- Technically speaking, shareholders have a convex claim. Increasing the risk of the firm increases the expected value of the equity!

This simple example clearly shows the different risk preferences of debt- and equityholders. While it is often in the best interest of debtholders to avoid risks, shareholders of firms with debt financing have a strong preference for risk.

This can lead to the so-called asset substitution problem:

- Let's assume that that the firm is currently valued at 700. Let us also assume, for the moment, that the firm is fully equity financed, so that the chart to the left ("Firm payoff") is the relevant payoff chart for the shareholders.

- Now the shareholders are confronted with the following project: They can invest 700 today into a project that generates a payoff of 5'000 in 1 year with probability 10%, and a payoff of 0 with probability 90%.

- For simplicity, let us also assume that interest rates are 0 so that we can ignore discounting.

Will the shareholders take the project? The answer is (hopefully) no, because the project costs more (700) than it is expected to generate (500). Therefore, it's Net Present Value (NPV) is negative (-200):

Required investment today = 700

Expected payoff = 0.1 × 5'000 + 0.9 × 0 = 500

Net Present Value = -Investment + Expected payoff = -700 + 500 = -200.

If the shareholders take the project, the value of their claim on the firm will drop by 200 from 700 to 500. Rational shareholders will therefore avoid the project.

But what if the firm has the financing structure discussed above (i.e., 700 of debt outstanding)? Will the answer change?

The following graph shows the payoffs to the debt and equityholders with and without the project.

| Without project | With project | |||

| Success (10%) | Failure (90%) | Expected | ||

| Total firm payoff | 700 | 5'000 | 0 | 500 |

| Debt payoff | 700 | 700 | 0 | 70 |

| Equity payoff | 0 | 4'300 | 0 | 430 |

Discussion:

- Without the project, the full current value of the firm (700) will go to the debtholders and there will be nothing left for the shareholders.

- The picture changes dramatically if the firm pursues the project:

- With 10% probability, the project will be a success and generate a payoff of 5'000. Of that payoff, 700 are used to satisfy the debt claims and the rest, 4'300, go to the shareholders.

- With 90% probability, there will be nothing left to distribute.

- The expected total firm payoff is the same as in the case of the fully equity financed firm, namely 500. So the conclusion remains that this is a bad project, since it reduces firm value from 700 to 500. But debt- and equityholders are not equally affected by this value destruction:

- Debtholders will recover their claim in only 10% of the cases. So their expected value drops by 630 from 700 to 70.

- The shareholders, in turn, expect a residual claim of 4'300 in 10% of the cases, so their expected value increases from 0 to 430!

Consequently, if shareholders are in charge and if they are rational, they will take the project and make money by destroying money! In the above example:

- The overall value destruction of the project is 200 (i.e., the decline in firm value)

- However, the project allows shareholders to redistribute wealth of 430 from the debtholders into their own pockets.

- The total loss for the debtholders is therefore 630; the total gain for the shareholders 430.

This is the so-called Asset Substitution Problem. In the presence of debt financing, shareholders might have an incentive to increase the riskiness of their assets, even if that means that the firm destroys value. The source of the problem lies in the asymmetric payoffs that we have seen before: Shareholders have an unlimited upside potential (the positive manifestation of risk) whereas they share the downside risk (the negative manifestation of risk) with the debtholders.

In more plain terms: in the presence of (substantial) debt financing, shareholders play with other people's money (namely that of the debtholders).