Reading: Payout Basics

2. What are Dividends?

2.3. Dividend Taxation

It is important to note that dividend income is generally taxed twice:

- The first taxation occurs at the corporate level, since dividends constitute a distribution of after-tax earnings to shareholders.

- The second taxation occurs at the shareholder level, since dividends constitute a taxable income for many shareholders.

This is the so-called double taxation of dividends.

For example, consider a firm that generates pre-tax earnings of 1'000. Suppose the corporate income tax is 30% (τC) and shareholders are subject to a tax rate of 15% on dividend income (τD). This constellation has the following tax implications:

- The firm will be subject to a corporate tax of 300, that is, the pre-tax eranings of 1'000 times the corporate tax rate of 30%.

- The remaining 700, the firm's net income, can be paid out as a dividend. Given an dividend income tax of 15%, the dividend payment increases the shareholders' income tax bill by 105 [= 700×0.15]. Consequently, the after-tax dividend received is 595.

- A pre-tax earning of 1'000 therefore transforms into an after-tax dividend of 595. The overall tax rate is therefore 40.5%.

The combined corporate and dividend income tax rate is sometimes referred to as integrated corporate tax rate:

Integrated corporate tax rate = \( \tau_C + \tau_D - \tau_C \times \tau_D = 0.30 + 0.15 - 0.30 \times 0.15 \) = 40.5%.

Qualified taxation of dividends

To limit the degree of double taxation, many countries have special tax brackets for qualified dividend income. In the U.S., for example, qualified dividends are taxed at the same rate as capital gains: Put differently:

- Investors in an income tax bracket at or below 15% pay 0% taxes on qualified dividend income;

- Investors in income tax brackets between (and not including) 15% and 39.6% have a 15% tax rate on qualified dividends;

- and investors in the 39.6% income tax bracket pay a 20% tax on qualified dividend income.

To qualify for these lower rates, the dividend (1) must have been paid by a U.S. corporation (or a qualifying foreign corporation), (2) is not listed with the IRS as a non-qualifying dividend, and (3) the shareholder in question has held the share for more than 60 days (90 days in the case of preferred stock).

Dividend exclusion

A similar mechanism applies for stocks that are held in corporate structures (corporations owning stock of other corporations). In this case, domestic corporations in the U.S. can exclude a certain portion of the collected dividends from their taxable income (so-called dividend exclusion).

- If the corporation owns less than 20% of the dividend-paying firm, the dividend exclusion is 70% (that is, 70% of the collected dividends are tax free)

- If the company owns more than 20% of the dividend-paying firm, the dividend exclusion is 80%.

International comparison

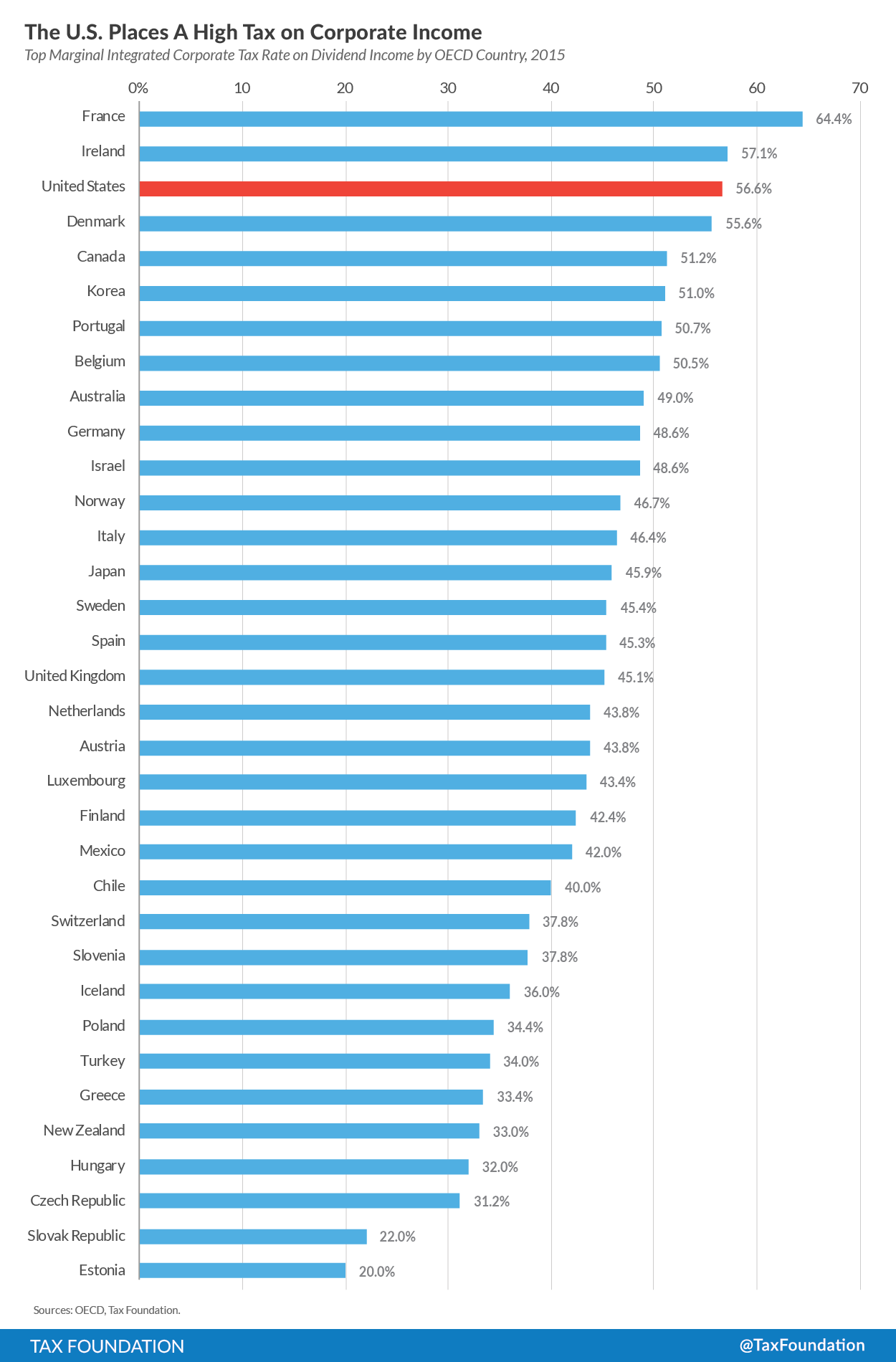

The following graph shows a cross-country comparison of the integrated corporate tax rate, according to OECD and Tax Foundation:

Corporate income taxation in the United States

Until 2017, the U.S. statutory tax rate on corporate income was 39.1% (τC) and the maximum combined federal and state dividend income tax rate (τD) was 28.7%. This implied a maximum integrated corporate tax rate of 56.6% [= 0.391 + 0.287 - 0.391×0.287], one of the highest in the world. Put differently, each dollar a company earned could generate a tax bill of as much as 56.6 cents before arriving in the pockets of shareholders.

Under the revised tax plan passed by the United States Congress in December 2017, the federal income tax dropped to 21% while maintaining the maximum federal dividend income tax rate at 23.8%. At the federal level, this consequently lowered the maximum integrated tax rate to 39.8% [= 0.21 + 0.238 - 0.21×0.238]. With this significant tax cut, the U.S. integrated tax rate now is considerably lower than that of most of its peer countries, including Canada (51.3%), Germany (48.6%), U.K. (45.1%), or Japan (45.9%).