Reading: Dividends vs. Share Repurchases

2. Flexibility

Buybacks are a more flexible form of payout than dividends. In this context, various dimensions of flexibility are relevant:

- Timing of distribution

- Recipients of distribution

- Long-term commitment.

Timing of distribution

As we have seen in the section Payout Basics, dividend payments follow a clearly defined timeline. Once approved by the board or the shareholders' meeting, a clearly defined payment must be made to all shareholders on the promised date.

Buybacks, in constrast, offer much more flexibility, especially in the case of open market buyback programs. Within the limits of the law, the firm can freely choose when they repurchase shares and how many shares they repurchase. They can repurchase when conditions are favorable (for example, because the stock price has dropped), and they can simply cancel the program when conditions are unfavorable.

Recipients of distribution

Buybacks are also more flexible form of distribution from the point of view of the shareholders. With a dividend, all shareholders receive a cash consideration, regardless of their actual cash needs. This brings about potential adverse tax effects as well as transaction costs for those shareholders who want to reinvest the proceeds in the company. Dividends are therefore often rather "sticky."

In contrast, a buyback program triggers a cash consideration only for those shareholders who decide to participate in the program. Therefore, a buyback program factually grants shareholders the right to choose between a cash consideration and a larger ownership stake in a (smaller) company.

Long-term commitment

Finally, dividends are often viewed as a long-term commitment to shareholders. Once initiated, firms are very reluctant to cut dividends, as this is generally interpreted by market participants as a signal of failure. This signal can have a strong impact on the firm's stock price. For example, Bessler and Nohel (1996) find that stocks drop by more than 10% in the two-week period surrounding dividend cuts.

Therefore, firms are generally rather careful when increasing their ordinary dividend payments, as it is generally understood that they are expected to at least maintain that level of dividend for the foreseeable future.

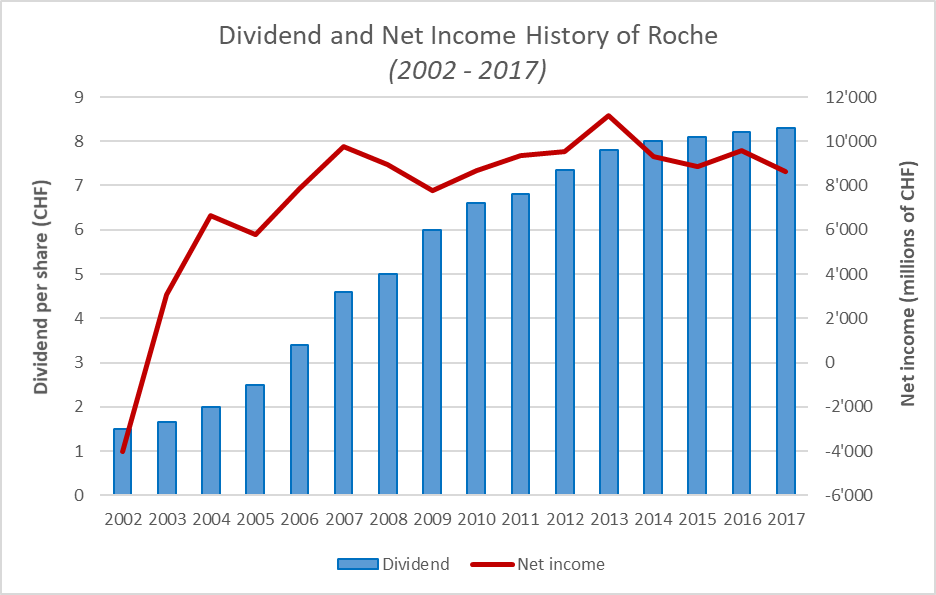

A case in point for this behavior is Switzerland's Roche, which announced in March 2018 that it would increase its annual dividend to shareholders for the 31st consecutive year. The graph below shows how smoothly Roche has adjusted its dividends per share between 2002 and 2017 (blue bars, left axis) and compares this evolution with that of the firm's net income (red line, right axis).

As we will discuss in more detail further down, a firm can use this perceived commitment to signal the market that it is confident about its financial prospects.

However, and by the same logic, it follows that an adjustment of the ordinary dividend is generally the wrong instrument to make an extraordinary distribution to shareholders. To this end, firms could declare extraordinary dividends (such as anniversary dividends), or they could announce a share buyback program, wich is not considered a long-time commitment by the market.