Reading: Dividends vs. Share Repurchases

7. Tax Considerations

7.5. Discussion

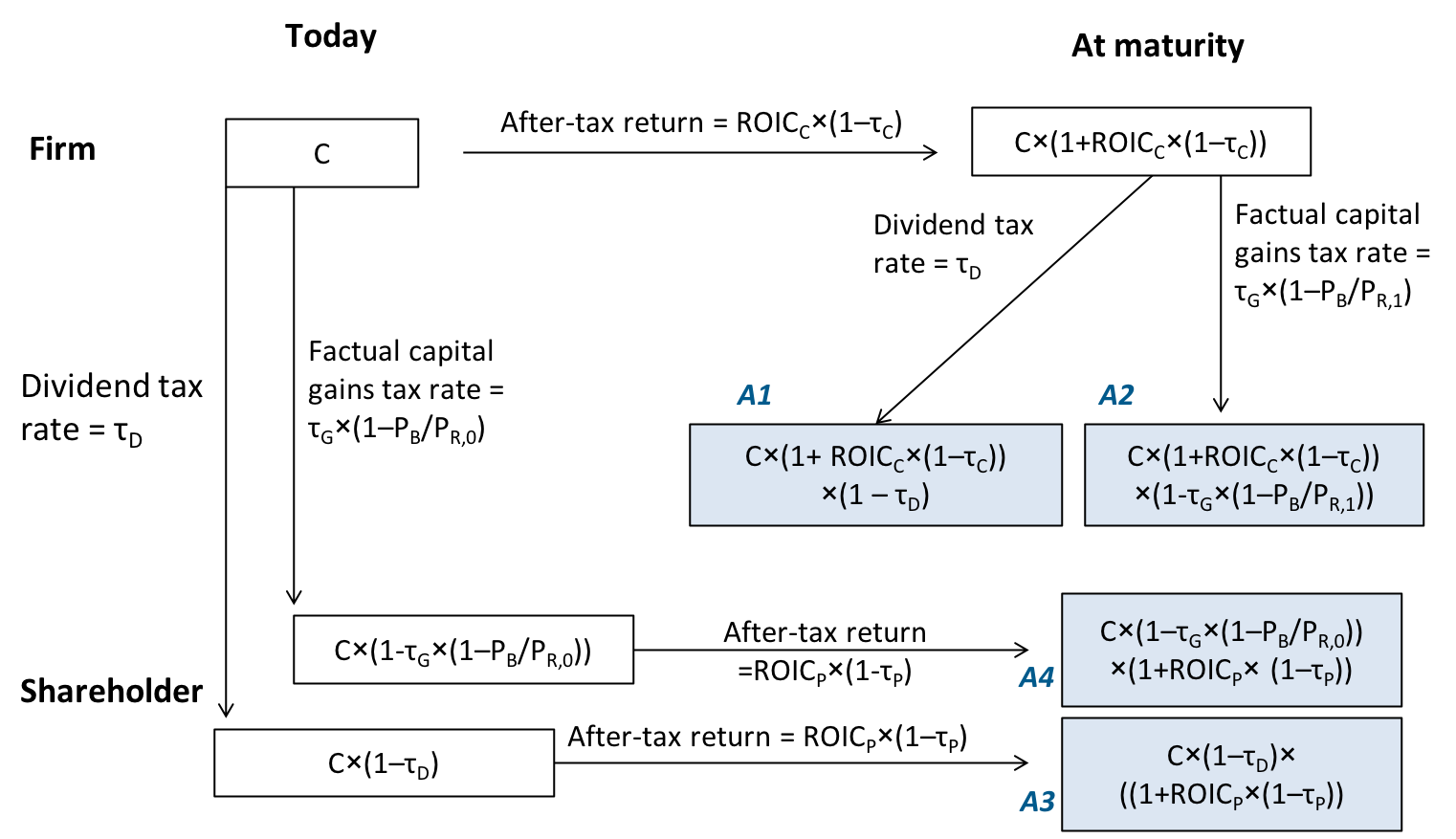

By now, we have studied the relevant tax trade-offs with respect to how much and how to return money to the shareholders. Very formally, the four alternatives that we have considered are summarized in the chart below:

- A1: The firm reinvests the excess cash and then returns the money as a dividend payment

- A2: The firm reinvests the excess cash and then returns the money via share buyback

- A3: The firm pays a dividend today and shareholders then invest on their own

- A4: The firm repurchases shares and shareholders then invest on their own

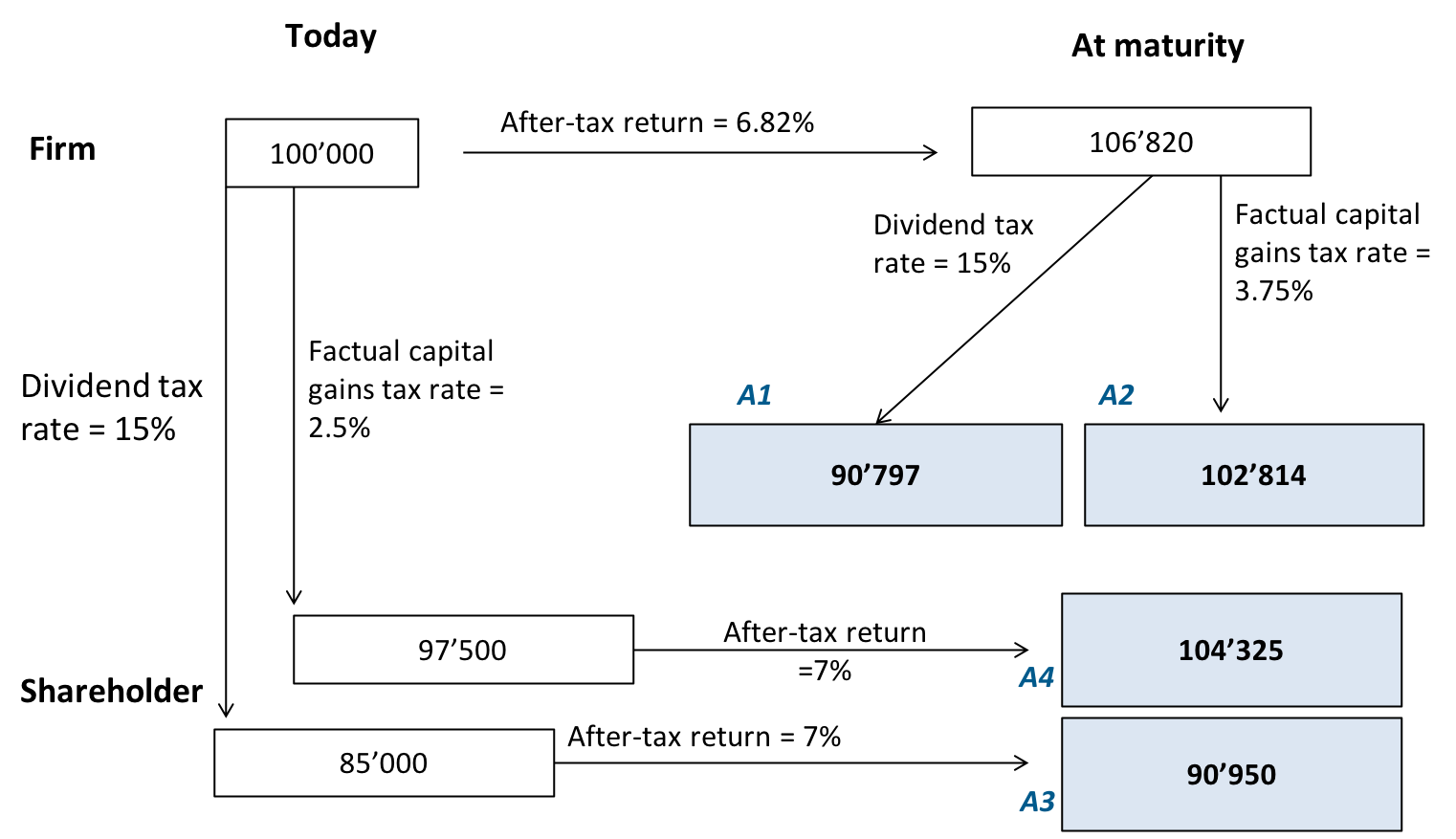

Based on the assumptions in our example, the main results can be summarized as follows:

The main findings can be summarized as follows:

- In our example, the most valuable alternative is to repurchase shares today and then have shareholders invest the proceeds on their own. In contrast, the least attractive alternative is to reinvest the funds in the company and then return them as a dividend in one year.

- One can also see that the financial differences between the various alternatives are rather striking. For example, the payoff of the most valuable alternative exceeds that of the least valuable alternative by almost 15%.

- The main driver of these differences are the different tax treatment of dividends (fully taxed) and buybacks (partially taxed).

- Interestingly, the firms should return money to its shareholders today, despite the fact that the firm's reinvestment return ROICC of 11% is larger than the shareholders' ROICP of 10%!

- This is because the ROIC is a pre-tax return.

- Since in our example, the corporate income tax rate (38%) is considerably larger than the personal income tax rate (30%), the shareholder's after-tax ROIC (7%) is actually larger than that of the firm (6.82%).

- Put differently, because of taxes, it will make sense to forego the comparatively attractive investment project (ROIC of 11%) and, instead, put the money in a less attractive project (ROIC of 10%). Taxes could therefore distort investment decisions and lead to an overall suboptimal capital allocation.

- Therefore, we have to slightly adjust the management recommendation from the preceding section, where we said that firms should retain funds if their ROIC exceeds the cost of capital (i.e., the shareholders' ROIC). This statement is still true, we simply have to measure ROIC on an after-tax basis!

The relevance of corporate income taxes

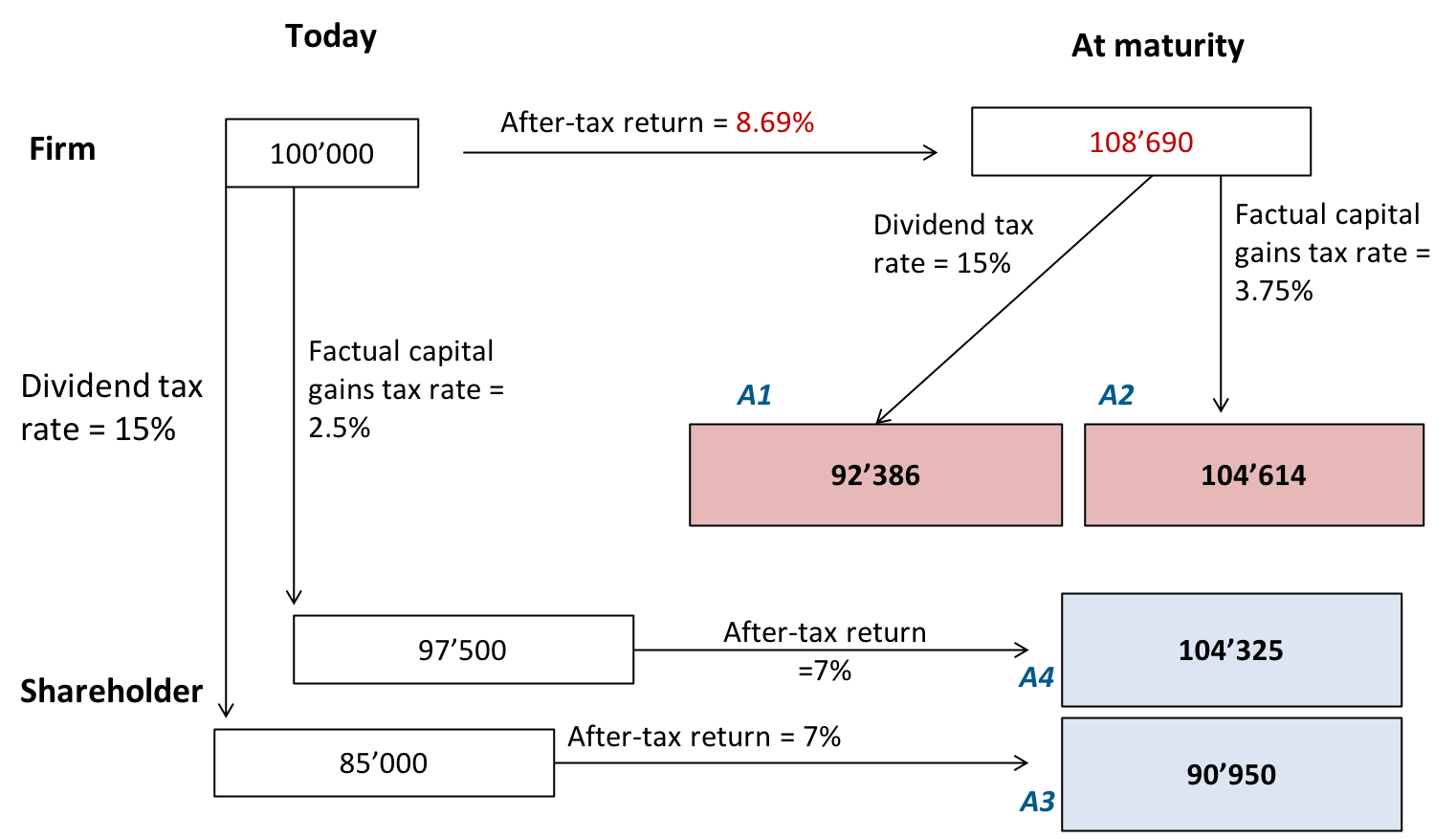

We can use the example to illustrate the relevance of corporate (vs. personal) taxes in the payout decision. In particular, we can investigate how the 2017 cut of the federal corporate tax rate to 21% should affect that decision in theory. To this end, we can re-run the analyses from the preceding section and simply reduce the corporate income tax rate (τC) from the assumed 38% to 21%.

- The firm's after-tax ROIC increases from 6.82% to 8.69%: \( \text{After-tax ROIC}_C = ROIC_C \times (1 - \tau_C^*) = 0.11 \times (1 - 0.21) = 0.0869 \)

- Therefore, shareholders are better off if the firm retains the funds, as its after-tax ROIC exceeds that of the shareholders (still 7%).

- The following figure summarizes the key trade-offs under the new assumptions (in red):

Basic management implications

By now we have discussed the most important facets of the payout decision. Put very simply, it can be boiled down to the following two key messages:

- Payout vs. reinvestment: Firms should reinvest if the after-tax reinvestment return exceeds the after-tax reinvestment return of the shareholders (i.e., the after-tax cost of capital). Otherwise, they should return the money to shareholders.

- Dividend vs. share repurchases: Firms should pay dividends if the shareholders' dividend income tax rate exceeds the factual tax rate for buybacks, i.e., the fraction of the buyback price that reflects a capital gain times the capital gains tax. In many countries, this puts buybacks at a significant tax advantage over dividends.

In reality, however, the situation is often less clear cut:

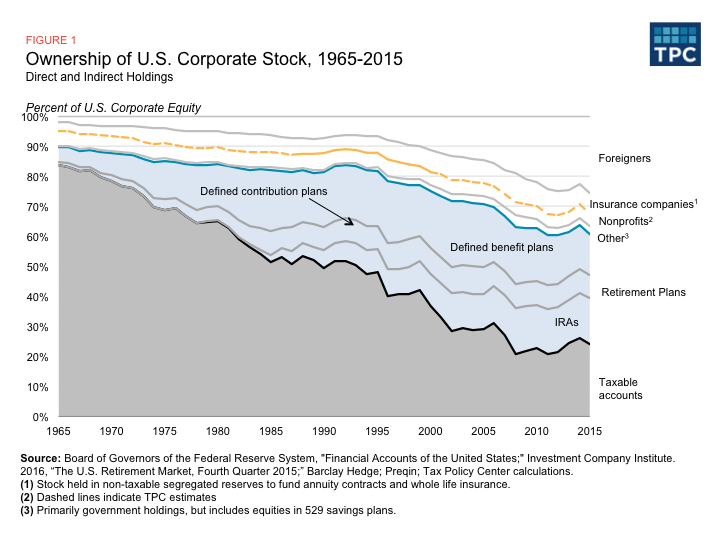

- Different investors have different tax rates. Some investors could be individuals, others could be corporates, mutual funds, trusts, retirement plans, or foreign entities. In fact, a 2016 report by the Tax Policy Center reveals that the taxable shareholder base has decreased dramatically over the last few decades, from more than 80% in the 1960ies to about 25% in 2016. Put differently, approximately 75% of U.S. stocks are held in accounts that are tax exempt or only partially taxed!

- Moreover, different investors might have bought at different prices, so that some will face higher capital gains taxes when participating in buyback programs than others.

- Different investors might also have different investment opportunities (ROIC). This is an often-heard argument in the context of venture capital or private equity. There, the typical investment horizon is around 5 to 7 years. After that, (surviving) firms mature and the professional investors want to exit to put the money back to work in another promising venture. In our terminology above, the implied argument is that the investor's ROIC will eventually exceed that of the mature firm, which is why investors want to exit.

The bottom line of all these considerations therefore is that there is typically no single one correct distribution policy. We have discussed many of the aspects that should enter the equation, and we will continue to do so in the following section.