Reading: Forms of Takeover

4. Mergers

In a merger, the acquiring company, and possibly also the target company, continue to exist as legally independent entities. There are two main types of mergers:

- Statutory merger: In a statutory merger, the acquiring firm absorbs the assets and liabilities of the target company and the target company ceases to exist.

- Subsidiary merger: In a subsidiary merger, in contrast, the target company remains a legally independent entity and becomes a legally independent subsidiary of the acquirer.

Let's look at the two types of mergers in our example.

Statutory Merger: Cash Deal

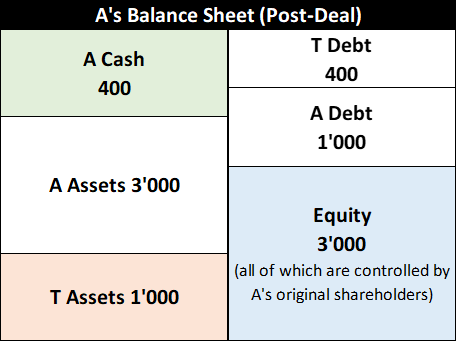

For simplicity, let us stick to cash transactions and let's assume that the acquiring company A buys the shares of the target company T at the current market value of 600. Consequently, the acquirer's cash balance drops by 600 from 1'000 to 400. After the acquisition of T's shares, A absorbs T's assets and liabilities. Consequently, the balance sheet changes as follows:

- Cash drops by 600 (the purchase price paid to the original shareholders of T)

- The (operating) assets increase by 1'000 through the absorption of T's operating assets

- Debt outstanding increases by 400 through the absorption of T's pre-takeover debt.

Statutory Merger: Stock Deal

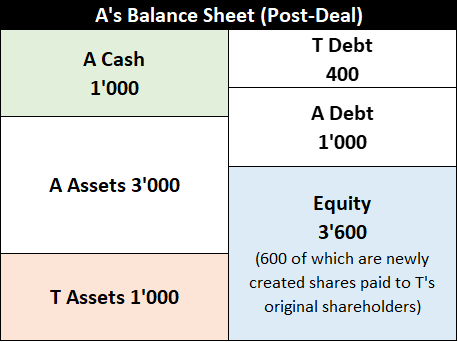

At the other end of the financing spectrum, the acquiring firm could issue new shares with a value of 600 and use them to purchase the target's shares. Instead of a cash consideration, the target shareholders would therefore receive shares of the acquiring company and the acquirer's cash balance would remain unaffected.

After this stock deal, A's balance sheet would therefore be:

Note that the resulting balance sheet is the same as in the case of the statutory consolidation that we have considered before. The only difference is that the legal entity is the surviving company A and not the newly created company New Comp.

The main implications of statutory mergers are as follows:

- After the deal, one, but only one, of the merging firms survive.

- Consequently, the accounts of the two companies are merged and there is no longer a separation between the acquirer's and the target's assets and liabilities.

- In a cash-only transaction, the target's shareholders receive a cash consideration of 600. After the deal, they do no longer own shares in the merged companies.

- Consequently, the shareholders of the acquiring company A will control the merged firms after the deal.

- A statutory merger can also be structured as a stock deal, in which the target shareholders become partial owners of the acquiring firm.

In the section Acquisition Price and Value Implications further down, we will take a closer look at cash vs. stock deals and their implications for the allocation of value and control after the deal.

Subsidiary Merger: Cash Deal

In a subsidiary merger, the acquiring company purchases the shares of the target company (with cash, shares, or other considerations) but then keeps the target company as an independent legal entity. In a sense, all that changes is that the shareholders of the target company receive a consideration.

Within the target company itself, it could be that nothing happens at all. Both firms keep their own accounts and at the end of the business year, firm A simply prepares consolidated accounts of the controlled entities.

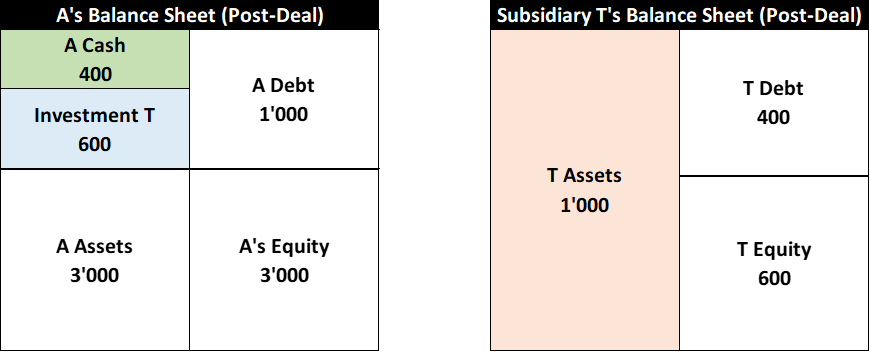

After a cash-only deal, in which the acquirer pays the target's shareholder a total cash consideration of 600, the balance sheets of the involved entities are as follows:

- The target T's balance sheet is unaffected, as only the ownership of that company has changed. Put differently, T's equity of 600 is now owned by A and no longer by T's original shareholders.

- A's cash balance drops by 600 because of the stock acquisition

- A has a new asset, namely an investment in T with a total value of 600:

At year end, A then prepares a consolidated balance sheet with its (legally independent) subsidiaries:

Subsidiary Merger: Stock Deal

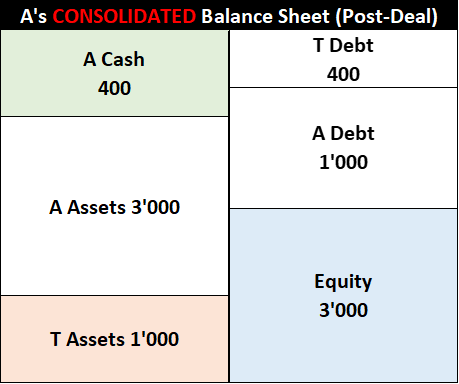

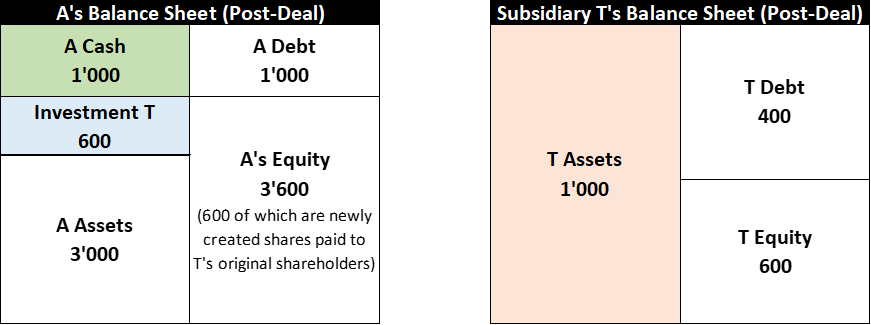

Alternatively, if the firm engages stock deal and pays 600 newly created shares to acquire T's shares, the acquirer and subsidiary balance sheets would look as follows:

And A's consolidated balance sheet would be:

Discussion

In our simplified example, the various forms of merger (in the case of stock deals) and the consolidation factually yield the same balance sheets of the combined entities. However, this does not imply that the transactions are identical:

- A statutory consolidation signals the strongest commitment of the participating firms. Both firms lose their "identity" and then typically operate under a new name. The transaction also signals a strong form of partnership and equality, as the two firms join forces in a new entity.

- Also a statutory merger signals a strong commitment, as the target company legally becomes a part of the acquiring company. However, there is usually also a clear signal that the acquirer is the stronger partner in the relationship. This could be challenging when integrating the merged companies, for example because of loss of identity by the employees of the acquired companies or perceived superiority (winner vs. loser) by the employees of the acquiring company.

- Finally, a subsidiary merger signals the weakest commitment, as the target company remains a legally separate entity. In principle, the acquirer could simply sell the target's shares to dispose of the company. At the same time, the subsidiary merger is the easiest to monitor, as the acquired company remains its own books and governance structures.