Reading: Initial Offer Price

2. Purchase Price Range

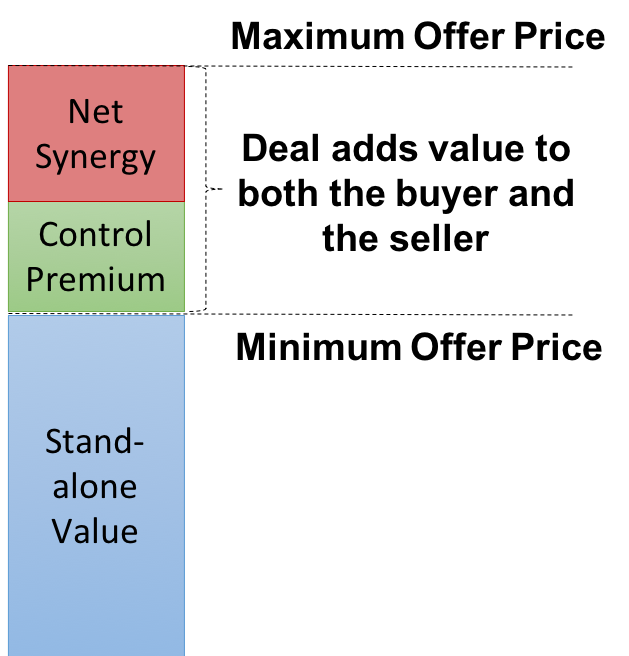

What's the minimum price the acquirer has to offer to be considered? And what's the maximum the acquirer can pay for the deal to still add value? The preceding valuations provide important answers to these questions.

Often, it is helpful for the buyer to think about this purchase price range as it indicates the price range within which the transaction adds value to both the buyer and the seller. Therefore, the price range factually defines the room of negotiation to find an agreement between the parties.

Minimum offer price

- Very generally speaking, the minimum offer price should correspond to the target's best alternative if there is no agreement with the buyer in question. If a potential acquirer's bids is less valuable than the target firm's alternative option(s), it will not constitute the target's best possible deal and will therefore generally not be considered. When entering negotiations, it is therefore always crucial to know your alternatives. Fisher and Ury (1991, Getting to Yes: Negotiating Without Giving In) named this critical element of the negotiation phase coined BATNA, which stands for best alternative to negotiated agreement.

- In many instances, the target firm's best alternative will to remain an independent company and to keep operating under the current business model. Therefore, the stand-alone value will offer valuable information about the minimum offer price.

- It could also be that multiple bidders are interested in acquiring the target company in question. If a new bidder enters the arena, it will usually have to top the best offer from the other bidders to be considered. In such situations, the minimum offer price therefore corresponds to the highest offer from other contestants.

- Clearly, having multiple bidders is attractive for the selling company, as this can result in a bidding war among the contestants. Therefore, one of the key tasks for the seller (or its bankers) is to create demand for the company in question. Such bidding wars are quite common in large public transactions.

- A case in point is the fight between Comcast and Fox to gain control over Sky in 2018. An initial offer from Fox valued Sky at GBP 18.5 billion. Comcast then topped that bid with a GBP 22 billion offer, which Fox then outbid again. Ultimately, Comcast offered GBP 26 billion, which is 40% more than Fox's initial bid. It is not a big surprise that the stock price of Sky has increased tremendously since the bidding war erupted.

Maximum offer price

- In contrast, the maximum a reasonable buyer should be willing to pay is the target company's stand-alone value plus all the benefits that are expected to arise from the deal (control premium plus net synergy).

- At such a valuation, the acquirer pays the full price. Such a deal does not add any extra value for the acquiring shareholders (it is a deal with an Net Present Value, NPV, of zero).

The Purchase Price Range

If the maximum possible offer price exceeds the minimum realistic offer price, there is a purchase price range within which a transaction can add value to both the target and the acquiring firm (and for their shareholders):

In such a situation, it should be fairly easy to find a deal structure that is acceptable to both parties.

Example 1

Target firm T is currently valued at 100 million. It is optimally managed, so there is no control premium. Acquirer A is convinced that net synergies of 50 million could be created with a merger.

Based on this information:

- The purchase price range is between 100 million (minimum offer price) and 150 million (maximum offer price). Any price within that range adds value to both the target and the acquiring firm:

- If the parties agree on a price of 101 million, the target firm captures a value-added of 1 million and the acquiring firm captures a value added of 49 million

- If the parties agree on a price of 125 million, they split the value added equally—25 million for the target firm and 25 million for the acquiring firm.

- If the parties agree on a price of 150 million, all the benefits go to the target firm. For the acquiring firm, the deal is value neutral: It pays 150 million for a company that has a value of 150 million to the acquiring firm.

Example 2

How does the situation change if the target firm from Example 1 has a takeover bid of 160 million from another potential acquirer?

In this case, A's minimum offer price increases from 100 to 160 million: The target firm's BATNA is the other bidder's offer of 160 million. Since this minimum offer price exceeds A's maximum (reasonable) offer price, it will be difficult (but not necessarily impossible) to find a deal structure that is valuable for the acquirer.

It may sound overly simplistic, but managers should keep the following in mind when negotiating takeover prices:

NPV to Acquirer = Maximum Offer Price — Acquisition Price

NPV to Target = Acquisition Price — Minimum Offer Price

In the heat of the negotiations, the acquiring party sometimes forgets the first equation and bids more than it reasonably should (for example, by making overly optimistic assumptions about the control premium and the net synergies). Such deals destroy value for the acquirer at the moment they are signed.

Are deals possible if the Minimum Offer Price exceeds the Maximum Offer Price?

If the minimum offer price exceeds the maximum offer price, there is a so-called Valuation Gap.

Such a valuation gap is a very typical situation in a negotiation: Very often, negotiations start with a constellation where the seller declares a minimum acceptable price that is larger than what the buyer is willing to pay!

The module Deal Structuring discusses possible strategies to bridge such valuation gaps, in particular:

- Find and correct the reason for the valuation gap (disclosure of information, discussion of key assumptions, etc.)

- Find an ownership structure that accommodates the gap

- Find a contractual solution that accommodates the gap (for example, an earn-out clause for the seller).