Reading: Acquisition Price and Value

5. Different Market Expectations

The previous sections have shown that cash-only deals, stock-only deals, and cash-and-stock deals can be structured in a way that the have the same value implications for the acquirer and the target. We have also mentioned that this is generally the case if the market agrees with the management's assessment of the deal, especially the expected synergies that result from the deal.

In this section, we now take a closer look at this issue. What if the market disagrees with the management expectations? As it turns out, such disagreement is fairly common. In particular, it often seems to be the case that the market is a bit less optimistic about the expected synergy potential than the management.

Let's go back to the example from before and let us assume that the management publicly announces the deals as we have considered them:

- Version 1: Firm A acquires Firm T for a total cash consideration of $900 million or $30 per share.

- Version 2: Firm A acquires Firm T in a stock-only deal. The target shareholders receive 1.667 newly issued shares of Firm A in exchange for 1 share of Firm T. In total, Firm A therefore issues 50 million new shares to the shareholders of T.

- Version 3: Firm A acquires Firm T. For each share, the current shareholders of T receive a cash consideration of $15 as well as 0.833 newly issued shares of Firm A. In total, this corresponds to a cash consideration of $450 million and 25 million newly issued shares of Firm A.

What happens if the market is less optimistic about the synergy potential of the deal?

In what follows, we assume that the market expects the deal to generate net synergies of $100 million instead of $500 million. Put differently, the market also believes that the deal makes sense (it adds $100 million in value). It is simply less optimistic than the management.

Post-Merger Valuation (EA*) and Stock Price (PA*)

With $400 million lower expected synergy gains, the market's assessment of the firm's post-merger equity value will be $400 below that of the management. For example, in the mixed deal (Version 3) that entails a cash payment of $450 million, the market expected post-merger equity value is only $1'850 million instead of $2'250 million:

Equity Value Merged Firm = EA* = Stand-Alone ValueA + Stand-Alone ValueT + Market Expected Net Synergy – Cash Payment = 1'600 + 600 + 100 – 450 = 1'850.

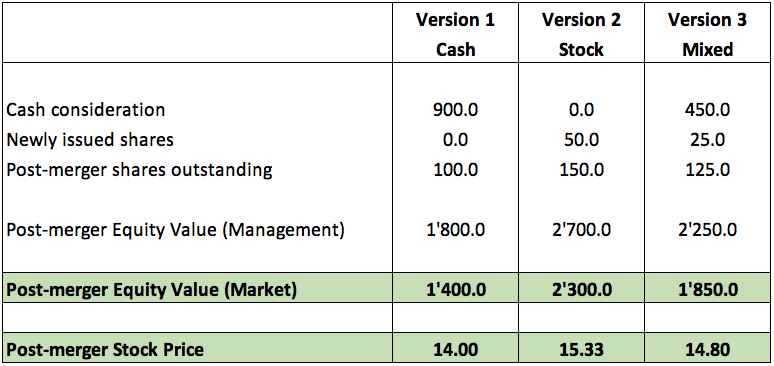

For the remaining two deal forms, the resulting market equity valuations are 1'400 in the case of a cash deal (instead of $1'800) and 2'300 in the case of a stock deal (instead of $2'700 million).

As per the announcements above (and the specific computations in the analysis of the three deal forms), we already know the number of shares that will be outstanding after the deal, namely 100 million in the case of a cash deal (0 newly issued shares), 150 million in the case of a stock deal (50 million newly issued shares), and 125 million in the case of a cash-and-stock deal (25 million newly issued shares).

With this information, we can now compute the Post-merger Stock Price of the acquiring company (PA*). In the case of the mixed cash-and-stock deal, that stock price will be $14.80:

Acquirer's Post-Merger Stock Price \( = P^*_A = \frac{E^*_A}{N^*_A} = \frac{1'850}{125} = 14.80 \)

The following table summarizes the three deal versions and resulting post-merger market equity valuations and stock prices:

The main takeaways are:

- As soon as the market expectations differ from the management projections, different deal structures will have different value implications.

- While the stock price goes to $14.8 in the case of the mixed cash-and-stock deal (down from $16.0 before the announcement), it goes to $14.0 with a cash-only deal and 15.33 with a stock-only deal.

- We also see that the larger the cash consideration, the larger is the movement in the stock price. The reason for this goes back to the risk-sharing argument that we made in the previous sections.

- For example, in the cash deal, the paid takeover premium of $300 million is "safe" for the target shareholders, in the sense that its value does not depend on the market's assessment of the deal's true value-added. For the acquirer, however, paying a cash premium of $300 million for a company that only justifies a premium of $100 million according to market expectations implies a value destruction of $200 million. Given 100 million shares outstanding, a $200 million value loss implies a drop in the stock price by $2 from $16 to $14.

- In contrast, the target shareholders share some of the risks in the deals that involve stock considerations. The reason is that the stock-deal structures that were designed by the management value the acquiring company's stock at $18.00.

- For example, in the stock-only deal, the target shareholders receive 50 million new shares because the total value of these shares would correspond exactly to the offer price of $900 million if valued at $18.00 per share (50 × 18 = 900).

- However, if the market values the merged company at only $15.33 per share after the stock-only deal (see table above), the total value of the target's stock consideration is only $766.7 million (= 50×15.33) instead of $900 million. Therefore, the acquirer factually "only" overpays by $66.7 million instead of $200 million in the cash deal.

- Put differently, with a stock-only deal, the acquiring shareholders incur a smaller loss ($66.7 million) than with a cash-only deal ($200 million loss).

Value Allocation and Deal Returns

With these considerations, we are now ready to summarize the three deal alternatives with respect to how they split the deal value among the acquirer and the target. This is shown in the following graph:

Here are some explanations to facilitate the reading of table:

- The first part of the table shows the total consideration that goes to the target shareholders.

- This total consideration corresponds to the cash payment associated with the three deal versions plus the newly issued shares of the acquiring company valued at the post-merger stock price from the first table above.

- We have discussed explicitly the considerations of the cash deal and the stock deal.

- In the mixed deal, the cash consideration is $450 million and the target shareholders receive 25 million new shares that have a value of 14.8 according to our initial computations, for a total consideration of $1'480 million.

- The second part shows the total value that goes to (or remains with) the acquiring shareholders. This is simply the post-merger stock price from the first table times the number of shares the acquiring shareholders own after the deal (i.e., 100 million shares).

- The third part then shows the Deal Value Added, which is simply the Deal Value from the first (target) and second (acquirer) part of the table minus the firm's pre-merger stand-alone value.

- For example, in the case of a cash deal, the total consideration is 900 million and the target's stand-alone value is $600 million. Consequently, the target's value added is $300 million.

- The same deal has a value added of -$200 million for the acquirer, given a stand-alone value of $1'600 million and a post-merger value of $1'400 million.

- Finally, the last part expresses the deal value added as a percentage of the pre-merger stand-alone value to compute the deal return.

- For example, the target's $300 million value added from the cash deal corresponds to a 50% return based on a stand-alone value of $600 million.

- Similarly, the acquirer's deal return is -12.5% given a value added of -$200 million on a stand-alone value of $1'600 million.

Discussion and Interpretation

- This example has shown that the deal structure matters as soon as the market expectation differ from the management expectations.

- In a cash-only deal, the risk of an over- or underestimating the deal synergies fully lies with the acquirer. The target shareholders are shielded from this risk. In contrast, in a deal that involves a stock consideration, the acquirer can partially share that risk.

- The higher the stock component, the larger the risk-sharing among the parties. This has important management implications!

- A cash deal sends a comparatively strong signal that the acquirer is confident about the synergy potential of the deal.

- If the deal parties have uncertainties about the synergy potential, or if the value of the net synergies critically depends on the target's future involvement, a stock payment might be more suitable because it leads to a better alignment of incentives.

- It is also important to note that all three deal versions have the same total value added, namely the (market expected) net synergies of $100 million that result from the merger.

- Economically, the deal therefore makes sense.

- The problem from the acquiring firm is that it overpays for these synergies.

- This leads to a value distribution from the acquiring firm to the target's shareholders. In the example that we have used, this value distribution is larger than the net synergies, which is why the deal destroys value for the acquiring shareholders.

- The latter is a very important distinction: The acquiring shareholders do not lose money because the merger destroys value. They lose money because they overpay for the merger's value-added.

- As we will see in the last course section, this is a rather typical situation. Often, it is not easy to create value with M&A transactions because they tend to overestimate the synergy potential (and underestimate the integration cost).

To practice our relatively simple M&A analysis model, the next section takes a look at a real case and shows how useful this model can be to better understand the key mechanics of M&A transactions.