Reading: Why Go Public?

3. Benefits of Going and Being Public

3.1. Direct Value Creation

The metamorphosis from a private to a public company often has a very direct positive impact on the value of the firm because it transforms an illiquid investment into a liquid investment. More specifically, the liquidity related sources of value are:

- Dissolution of liquidity discount

- Providing liquidity to current shareholders

- Making it easier for shareholders to diversify risk

In addition to better liquidity, it could also be that the issuing firm makes money because it manages to sell new shares at a time when these shares are in particularly high demand and therefore fetch a high price (Market timing). Below, we discuss these sources of value more in more detail.

Dissolution of Liquidity Discount

The fact that the shares of privately held companies cannot be traded freely implies that these shares constitute a relatively illiquid investment: It is difficult or even impossible to convert them into cash if cash is needed.

For this liquidity risk, shareholders want to be compensated: When investing in an illiquid asset, shareholders will generally require a higher return, the so-called illiquidity premium, than when investing in an identical asset that can be bought and sold freely. Because of this illiquidity premium, illiquid assets typically trade at a discount compared to otherwise identical liquid assets.

As we discuss in the course section on the relevance of liquidity, control, and synergy (Module Relative Valuation), the discount for lack of liquidity can be sizeable and often is in the magnitude of 30 - 50%. If the decision to go public dissolves this illiquidity discount, the value of the firm's equity increases accordingly.

Example:

The equity of a privately held firm is currently valued at $60 million and this valuation includes a discount for lack of liquidity of approximately 40%, according to the investment bankers. If the decision to go public dissolves the discount for limited liquidity, the value of the firm's equity should increase accordingly to $100 million, all else the same:

\( \text{Value}_\text{illiquid} = \text{Value}_\text{liquid} \times (1 - \text{Illiquidity Discount}) \)

Consequently:

\( \text{Value}_\text{liquid} = \frac{\text{Value}_\text{illiquid}}{(1 - \text{Illiquidity Discount})} = \frac{60}{1-0.4} = 100 \)

Therefore, the decision to go public would increase equity value by 67% (=100/60 - 1), which, of course, makes IPOs a very attractive exit route for financially oriented shareholders such as venture capitalists (VCs).

Liquidity to Current Shareholders

For the original shareholders, liquidity means that they can sell parts of their shares to finance consumption or diversify their financial risk (see below). Both aspects can be valuable.

As we discuss in the module growth financing, one of the most important sources of financing during the early stages of a company's life is to spend as little money as possible. The result is that founders and employees earn below-market salaries and therefore often have to forego consumption. By going public, the shares the founders and employees receive as a compensation for these low salaries become a valuable currency. Founders and employees can sell part of them to finance overdue consumption and bring their personal finances in order.

Risk Diversification

The ability to sell (parts) of the shares has also very important implications for the risk diversification of the founders. Up to the IPO, the founders generally have all their eggs in one basket—their whole financial wealth and their full human capital is invested in the firm. Therefore, they generally do not have access to the benefits that risk diversification offers, namely that a smart combination of different assets allows investors to earn higher returns at the same level of risk or achieve the same return at a lower risk.

In fact, lack of diversification can have far-reaching implications for the subjective value that founders attach to the shares of the company. As we discuss in great detail in the module Cost of Capital, in particular the section "What is Beta?", an often substantial portion of an asset's risk are specific to that asset in question and can be eliminated trough a proper combination with other assets. Only the part of the risk that cannot be diversified, the so-called systematic risk, is compensated by the market with a higher expected rate of return.

According to the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), the standard workhorse to estimate the cost of capital, it can be shown that an asset's systematic risk corresponds to its total risk (volatility) times the correlation between the return of the asset in question and the market return:

Systematic riskj = Total riskj × Correlation between j and Market

For example, if an asset in question has a total risk (volatility) of 50% and its return exhibits a correlation of 0.6 with the market return, the asset's systematic risk is 0.5 × 0.6 = 30%. If, at the same time, the market's risk is 20%, this implies that the asset in question is 1.5 times as risky as the market. This is the so-called beta coefficient in the Capital Asset Pricing Model:

\( \text{CAPM Beta}_j = \beta_j = \frac{\text{Systematic risk}_j}{\text{Market risk}} = \frac{0.3}{0.2} = 1.5 \)

Accordingly, the risk premium that investors expect to earn when holding the asset equals 1.5 times the market risk premium. Assuming a risk-free rate of 2% and a market risk premium of 6%, investors would therefore require a rate of return of 11% to hold the asset in question:

Cost of capital (CAPM)j = Risk-free return + CAPM Betaj × Market risk premium = 0.02 + 1.5×0.06 = 11%.

But what if an entrepreneur has no access to diversification because all her wealth is trapped in her company?

- For such an entrepreneur, the CAPM Beta is irrelevant because she has no access to diversification (because she has no money to invest in other companies)

- For her, the relevant risk of the asset is therefore the total risk, and not the systematic risk.

- If anything, she wants to be compensated for that total risk!

- Instead of the CAPM Beta, several authors suggest to use the so-called Total Beta in such situations. The total beta incorporates the full risk of the asset, and not only its systematic risk:

\( \text{Total Beta}_j = \beta_j = \frac{\text{Total risk}_j}{\text{Market risk}} = \frac{0.5}{0.2} = 2.5 \)

- In our case, given a total risk of 50% (instead of a systematic risk of 30%), the firm's total beta would therefore be 2.5 instead of 1.5!

- Using the same logic as above, the investor would therefore require risk premium equal to 2.5 times the market risk premium, which would boost the cost of capital from 11% to 17%:

Cost of capital (no diversification)j = Risk-free return + Total Betaj × Market risk premium = 0.02 + 2.5×0.06 = 17%.

To see the value implications such lack of diversification can trigger, suppose the firm in question is expected to earn a cash flow of 100 per year forever (just to simplify the computations). A perfectly diversified investor would apply the CAPM cost of capital to this future cash flow stream and therefore assign the firm a value of 909.

Value perfectly diversified = \( \frac{\text{Cash flow}}{\text{Cost of capital (CAPM)}} = \frac{100}{0.11} = 909 \)

In contrast, an investor that has no access to diversification, would tend to use a cost of capital of 17% and therefore value the firm at 588:

Value no diversification = \( \frac{\text{Cash flow}}{\text{Cost of capital (no diversification)}} = \frac{100}{0.17} = 588 \)

For the undiversified shareholder, the value of the firm is therefore 35% lower than for the diversified shareholder. Access to diversification via an IPO could resolve that discount at least partially and, therefore, improve the subjective valuation of the firm for the founders.

Market Timing

Firms often seem to take advantage of "windows of opportunity" when going public: They list their shares at times when market conditions are favorable and where there is a lot of demand and excitement about the IPO.

The evidence is that IPOs often come in industry clusters and IPO volume is highest near market peaks.

With such market timing, firms can sell their shares at a higher price and consequently make more money than if they went public under less favorable market conditions.

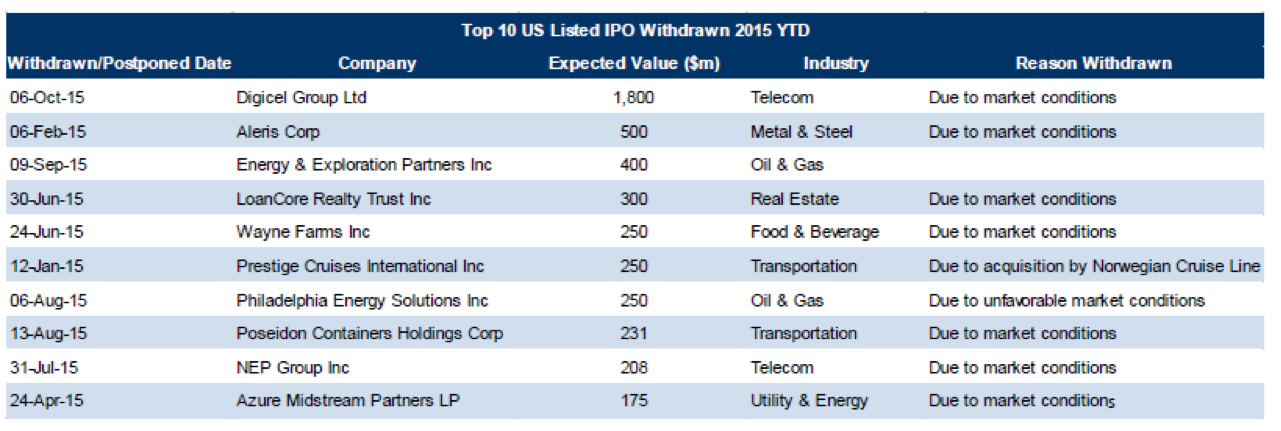

In fact, as the following figure shows, there is quite a significant number of firms that are ready to go public but then withdraw their IPO because of unfavorable market conditions. According to the figure, 8 out of 10 firms that withdrew their IPO in 2015 did so because of unfavorable market conditions: