Reading: The Going Public Process

6. IPO Underpricing

In the previous section, we have briefly addressed the issue of "underpricing," the fact that shares are typically sold at a lower price than the expected price on the secondary market. Given the prevalence of this phenomenon, this section takes a closer look at IPO underpricing and its possible reasons.

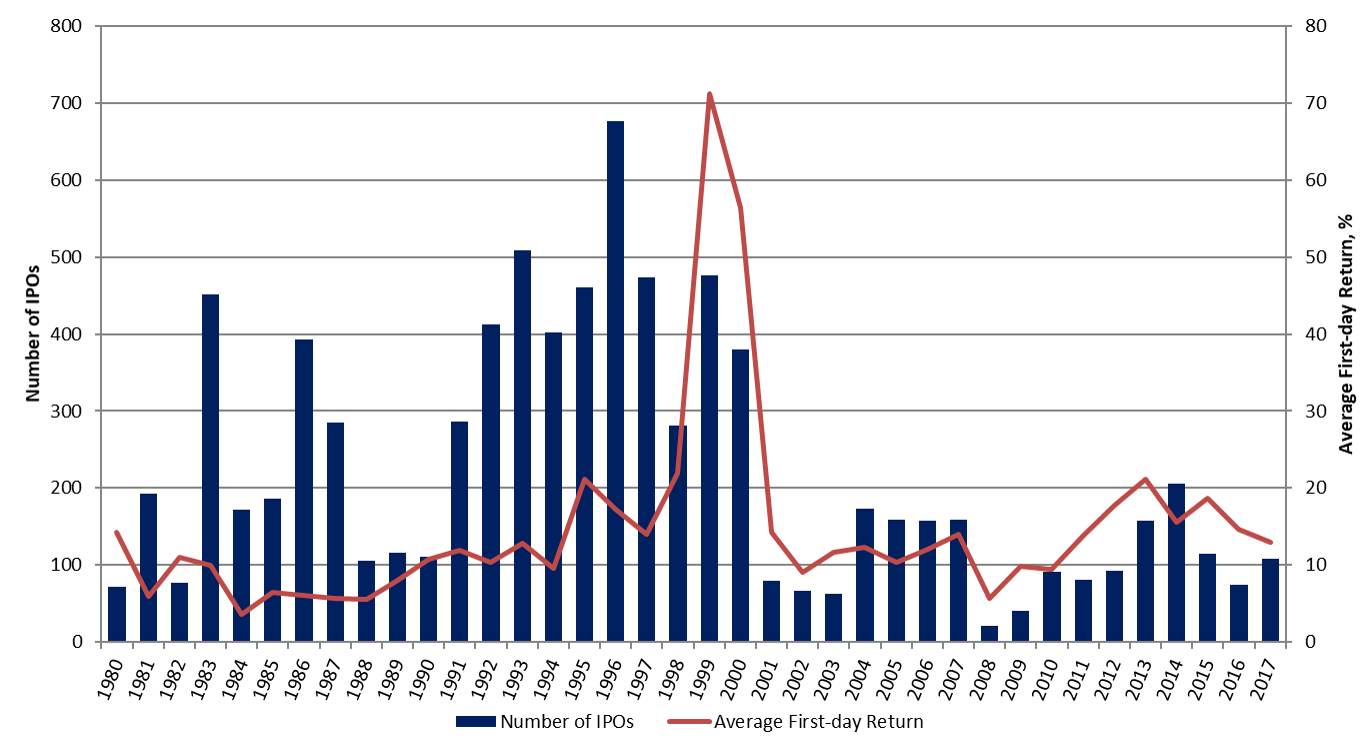

The following graph, which is from Professor Ritter's data library, summarizes the average underpricing of U.S. IPOs over the period 1980-2017.

More specifically, the red line shows the average return that IPO investors have earned in the past when buying shares on the primary market at the issuing price and selling them at the end of the first day of trading on the secondary market. This average first-day return is around 15%, on average! Put differently, by buying shares in an IPO and selling them one day later, investors, on average, earn a return of around 15%. Clearly, this is a very profitable investment strategy. However, it is usually one that is only open for large investors with good ties to the underwriting syndicate.

Another way to look at underpricing is to calculate the amount of money firms "leave on the table." For example, in the case of Dropbox, the underwriter placed 41.4 million shares at a price of $21. One day later, the shares were trading at $28.48 on the NYSE. The total amount of money left on the table refers to the money that goes to the IPO investors rather than the issuing firm. In the case of Dropbox, the money left on the table was $310 million (= 41.4 × (28.48 − 21.00)). That's how much more money the firm could have collected if the issue price were set equal to the subsequent stock market price.

Historically, the IPO with the largest amount of money left on the table was Visa in 2008, which issued approximately 400 million shares at a price of $44. After the first day of trading, the shares soared to $56.5. In total, the firm therefore left more than $5 billion on the table!

Reasons for IPO underpricing

There are various possible explanations for why underpricing is so persistently high:

- Underpricing makes the underwriter’s job easier and less risky: Obviously, it is much easier to sell securities if the investors know that these securities are systematically underpriced.

- Prevents costly lawsuits from investors: If the issue is overpriced and investors lose money on the first day of trading, they could sue the underwriters for misrepresentations. That is much less likely if investors make (a lot of) money.

- Opens indirect sources of income for the underwriting syndicate: Underwriters have great discretion in the allocation of shares, and they often use that discretion to allocate shares to their favorite customers. In order to become such a favorite customer and gain access to attractive IPOs, institutional investors such as hedge fund or mutual funds are willing to overpay on commissions. In many instances, these extra commissions flush more money into the banks than the 4-7% these banks collect with the underwriting discount!

- Could boost the demand for a firm’s seasoned offering (SEO) after the IPO: Underpricing also leaves a good taste with investors. If the firm needs additional equity in the future, investors might remember that good taste and, therefore, be more willing to invest.

- While the underpricing is factually paid by the original shareholders (see section on IPO and Value Allocation), these shareholders could be willing to accept a 15% haircut knowing that the IPO will give them access to liquidity and diversification (after the lock-up period). As we have argued before, liquidity and access to diversification can improve the value of an asset by much more than 15%.

- Underpricing could be necessary to attract uninformed investors (Rock’s hypothesis): Knowing that many large professional investors try to participate in good IPOs, uninformed investors might be reluctant to participate in the game. The reason is that the well-informed investors pursue the good IPOs aggressively, which reduces the uninformed investors' chance of receiving a share allotment in these good IPOs. Instead, they receive a disproportionately large allotment in the bad IPOs, as the well-informed investors ignore these. For an uninformed investor, receiving an allotment in an IPO therefore always also convey bad news: Nobody else wanted to buy these shares! This is the so-called winner's curse. By underpricing IPOs systematically, underwriters can address this issue and incentivize uninformed investors to still participate in the game.

- Finally, underpricing could be necessary to elicit information from potential investors (Benveniste and Spindt hypothesis). As we have argued above, the investors' participation in the bookbuilding process is an important price discovery mechanism for the underwriter. To incentivize investors to reveal that information, underwriters might have to offer them a positive return, on average. After all, these investors could just wait a few more days and then simply buy the shares in the secondary market.