Reading: The Going Public Process

8. Dutch Auction IPO

To tackle the hefty costs that are generally associated with the bookbuilding process, firms have looked for alternative ways to price and allocate their shares on the primary market. One such way is the so-called Dutch Auction IPO.

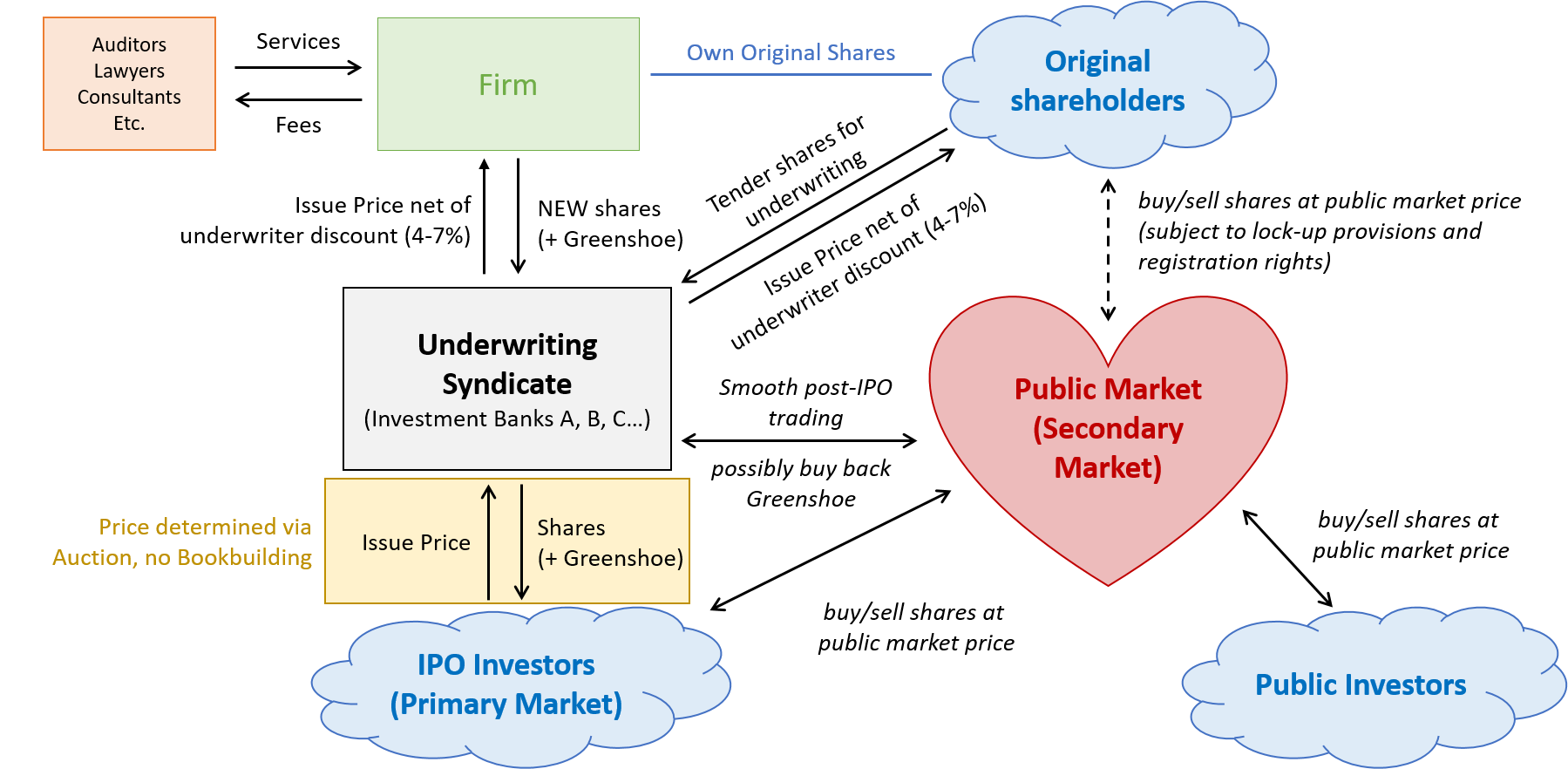

In principle, the structure of a Dutch Auction IPO is identical to that of the traditional IPO that we have discussed before: The firm hires an underwriter to place shares with primary investors before they start trading on the stock exchange.

The difference lies in the way the shares are priced and allotted to the primary investors: Instead of a bookbuilding process, the issue price is determined via auction and all investors who placed bid at a price equal to or higher than the issue price will participate in the IPO. The following graph summarizes the basic logic of a Dutch Auction IPO:

Let's look at the auction mechanism in a bit more detail:

- With a Dutch Auction, the underwriter and the issuer determine the number of shares to be placed with primary investors. They may indicate a price range for the shares, but they do not set a fixed price.

- Interested buyers submit bids, usually via online tool: They indicate the number of shares they want to buy as well as the price they are willing to pay. No bidder sees the other bids.

- Once bidding is over, shares are allotted from the highest bid down until all the shares are allotted.

- The price EACH bidder pays corresponds to the lowest price of all successful bids. For example, if the last successful bid is $40, all investors who bid a price higher than $40 will only have to pay $40 for their shares.

Example

Let's look at a simple example to better understand the auction mechanism. Suppose a firm wants to place 15'000 shares via Dutch Auction. The underwriter collects the following bids during the auction window:

|

Bid Price ($) |

Bidder |

Number of Shares |

Cumulative Number of Shares |

|

60 |

A |

1'000 |

1'000 |

|

58 |

B |

1'200 |

2'200 |

|

57 |

C |

1'500 |

3'700 |

|

56 |

D |

2'000 |

5'700 |

|

55 |

E, F, G |

4'300 |

10'000 |

|

54 |

H, I |

6'000 |

16'000 |

|

53 |

J, K, L |

6'000 |

22'000 |

|

52 |

M, N, O |

8'000 |

30'000 |

The highest bidder is Bidder A, who is willing to buy 1'000 shares at a price of $60. The second-highest bidder is Bidder B, who offers $58 for 1'200 shares. Etc.

The column to the right shows the cumulative number of shares that are demanded at the indicated price or a higher price. For example, bidders together are willing to buy a total of 2'200 shares at a price of $58 or higher (namely 1'000 at $60 and 1'200 at $58).

The task of the underwriter is now to set the issue price as the maximum price at which all 15'000 shares can be placed. As the table shows, that price is $54. As the column to the right shows, a total number of 16'000 shares can be placed at that priced, whereas the cumulative demand at the next higher price ($55) is only 10'000 shares. Consequently, the shares will be allotted as follows:

- The bids of Bidders A to G will be accepted in full. These bidders will buy the respective number of shares at the issue price of $54 (and not the actual price that these bidders were willing to pay!)

- The remaining 5'000 shares will be sold to Bidders H an I. Together, these investors have demanded 6'000 shares, so that their bids cannot be accepted in full. In most instances, these investors would therefore receive a pro-rated allocation. For example, if Bidder H wanted to buy 4'000 shares and Bidder I wanted to buy 2'000 shares, 3'333 shares would be allotted to Bidder H and 1'667 shares to Bidder I.

With the auction, the firm will end up placing all 15'000 shares at a price of $54.

Discussion

- Because the issue price is, in principle, determined by the auction mechanism and the shares are allocated to the highest bidders, the underwriters have much less control over the pricing and allocation of shares than in the traditional bookbuilding structure. Moreover, because all investors can participate in the bidding, the overall market ultimately determines the issue price in an auction. In contrast, the traditional bookbuilding often only involves the most favorite clients of the underwriters.

- Auctions would therefore seem to be a more efficient mechanism to discover the fair market price. Consistent with that, several studies show that the issue price of IPOs that use auctions is much closer to the subsequent stock market price than that of IPOs that use bookbuilding. For example, Lowry, Officer, and Schwert (2010) find that the average first-day return is 1.5% for auction IPOs and 33.5% for bookbuilding IPOs.

- Despite these apparent pricing benefits, Dutch Auction IPOs are extremely rare. According to Ritter (2018, Table 10), only 16 out of 1651 IPOs that took place between 2001 and 2016 used an auction mechanism. That is less than 1%. The remaining firms chose the traditional bookbuilding structure.

- There are several reasons why that might be the case:

- Underwriters are reluctant to advertise auctions because they lose fees and influence over the pricing and allocation process.

- Winner's curse: Another potential problem that plagues auctions is the so-called winner's curse, the fact that the winner of an auction tends to overbid. Especially in auctions with great uncertainty about the number of bidders, investors will find it hard to correctly adjust their bidding price to account for winner's curse. As a consequence, an auction with an unexpectedly large number of bidders will tend to be oversubscribed and overpriced, whereas an auction with an unexpectedly small numbers of bidders will tend to be undersubscribed. A study conducted by Sherman and Jagannathan (2006) finds support for that hypothesis.

- Free-rider problem: In the same study, the authors also inquire into potential free-rider problems that are associated with these auctions. As we have seen in the above example, the highest-bidding shareholders will receive an allocation of shares at a lower price that clears the offering. A potential strategy for uninformed investors could therefore be to bid a high price and free-ride on the informed investors, who conduct profound due diligence and bid a fair price. As long as there are not too many uninformed investors, the auction will clear at a "fair" price so that this strategy will allow the high-bidding uninformed investors to purchase shares at a fair price without incurring any costs to get informed. The informed investors, in contrast, bear the costs of information and also face the risk of a pro-rated allocation because their bidding price is comparatively low (but "fair"). This could induce informed investors to stay away from these auctions altogether.

- Finally, auctions are often less mechanical in reality than in the example above. Most importantly, it is often the case that the final issue price is set below the price that would allow the offer to clear. These are so-called "modified" or "dirty" Dutch Auctions. The purpose of this adjustment is to give the underwriter (and the issuer) back some wiggle-room in the allocation of the shares.

- Underwriters are reluctant to advertise auctions because they lose fees and influence over the pricing and allocation process.

Google's IPO in 2004

In 2004, Google offered to raise $2.718281828 billion (the number "e" to the ninth decimal point) via Dutch Auction IPO.

- The firm initially set a price range of $108-135 per shares

- Interested (institutional and private) investors were subsequently invited to bid via a web tool.

- The auction, however, was a failure:

- Demand was unexpectedly weak so that the offering price had to be revised down

- Ultimately, the firm sold shares at $85 (more than 20% below the original minimum price)

- It only sold 22.5 million shares so that the IPO raised $1.9 billion instead of $2.7 billion.

- At the first day of trading, the stock then closed at $100 (approximately 18% above the issue price), implying that the auction mechanism failed to achieve a value that is close to the subsequent stock market price.

There are several potential reasons for the failure of Google's IPO, and not all of them are associated with the Auction mechanism:

- First, Google had bad timing. Right before their IPO, other technology shares (including Yahoo) had suffered losses on the stock market, which hampered the enthusiasm for tech IPOs.

- Second, the Google's top executives were not very cooperative during the pre-IPO talks with investors. Allegedly, they refused to answer many questions and thereby failed to earn trust from the investing public.

- Third, the Playboy magazine published an interview with Google's co-founders during the cooling-off period, during which communication between the firm and the public is greatly restricted. This raised concerns about whether the IPO could take place as planned.

- Finally, it also seems that the lead underwriters of the offering, Credit Suisse and Morgan Stanley, had tried to actively sabotage the auction by telling their institutional investors that there is low demand for the offering and that they should place their bids at the lowest possible price of $85. Allegedly, they were afraid that a successful auction could induce other firms to choose an auction instead of a traditional bookbuilding, which would significantly harm the banks' future revenue streams.