Reading: IPO Mechanics

7. Extensions

7.2. Why IPO?

So why is it that firms are willing to accept the significant costs associated with an IPO?

In this last step, we look at one possible reason, namely the fact that the firm constitutes a comparatively more liquid investment after the IPO and therefore is less likely to be subject to severe lack of liquidity discounts.

For the sake of illustration, let us assume that our firm in question could raise the necessary funds from a private equity investor ($200 million to the firm and $100 million to shareholders who want to exit).

Let us also assume that such a private equity deal would be much cheaper, as it only involves direct costs of $1 million, and no underwriter discount and no underpricing.

The flip-side of the private equity transaction is that it does not convert the firm into a liquid investment. Consequently, we assume that the firm value that we have computed before would be subject to a lack-of-liquidity discount of 40%, so that the pre-money value of the firm is only $300 million as opposed to $500 million:

Pre-money Valueilliquid = Pre-IPO Valueliquid × (1 − Illiquidity discount) = 500 × (1 − 0.4) = 300.

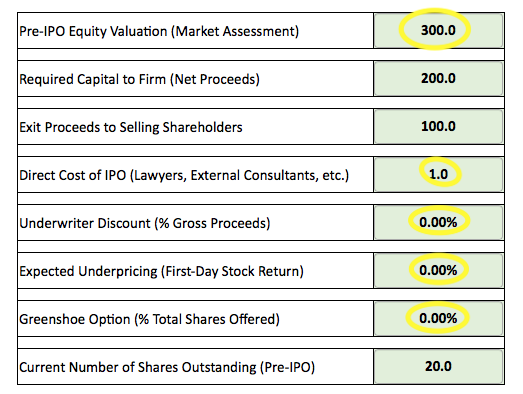

How do these changed assumptions about the firm's financing affect the value allocation? To find out, we can go back to our Online Tool "IPO Analytics." The following figure shows the revised assumptions for the private equity deal:

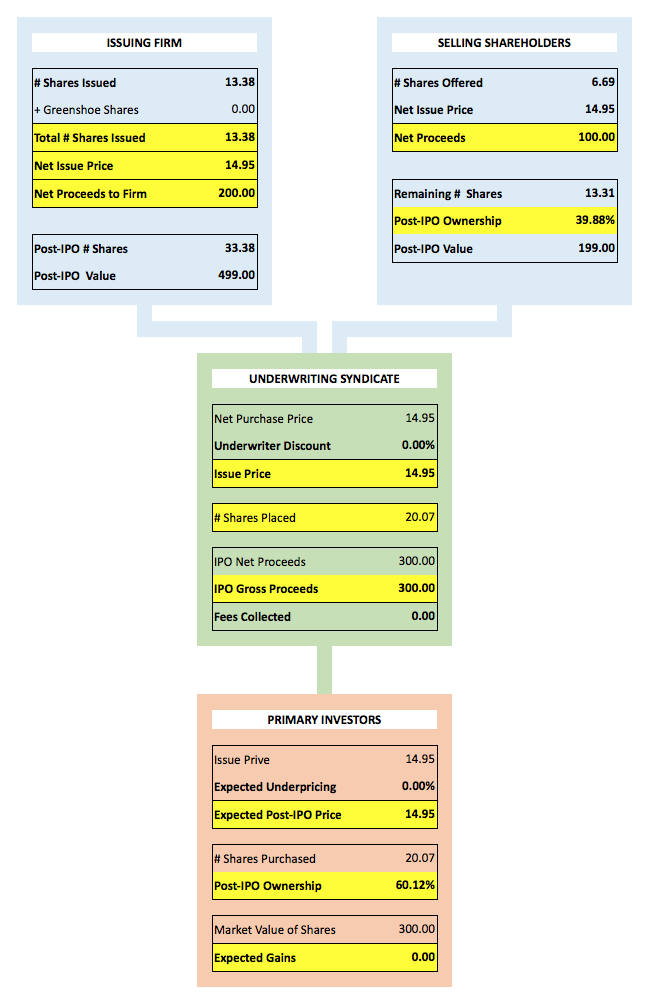

With these revised assumptions, we can now compute the relevant parameters of the private equity deal. The following screen shot from the Online Tool "IPO Analytics" shows the results. While the terminology is a bit misleading (there is no underwriter and no "IPO"), the actual numbers still drive the relevant points home.

As the figure shows, the costs of the private equity deal are indeed lower. There is no underwriter who collects hefty fees and the primary investors (the private equity firm) receive no underpricing, so that the net issue price corresponds to the post-financing stock price.

In total, based on our assumptions, the costs of the IPO are limited to $1 million in direct costs, compared to $86.6 million in the case of the IPO.

Still, conditional on our assumptions, shareholders are not better off with the private equity deal. The reason is that the base valuation is substantially lower ($300 million vs. $500 million) so that the private equity investors will ask for a larger share in ownership in exchange for their investment. Ultimately, the firm will give away a larger share (60.12% vs. 57.65%) of a less valuable firm ($499 million vs. $740 million). The result is that, after financing, the original shareholder will own a smaller and less valuable ownership stake compared to an IPO.

As we have argued before in the section on IPO underpricing, it could be that existing shareholders are willing to accept the hefty costs of an IPO because it transforms their remaining shares into a more liquid and therefore more valuable asset.