Reading: VC Approach

This chapter illustrates how venture capitalists often value young firms.

Valuation

In the previous section, we have tried to implement the DCF approach for startup companies. The DCF approach focuses on the long-term intrinsic value of the company. In many instances, however, investors might not really be interested in the firm's long-term value. They rather want to know how much someone else could be willing to pay for the company in 5-7 years, when they want to exit their investment. Put differently, they want to know the firm's potential exit value, that is, how much the investors will get if the business (or its assets) is sold at the end of the investment period.

Since this is the perspective many professional investors assume, this valuation approach is also known as the Venture Capitalist (VC) Approach.

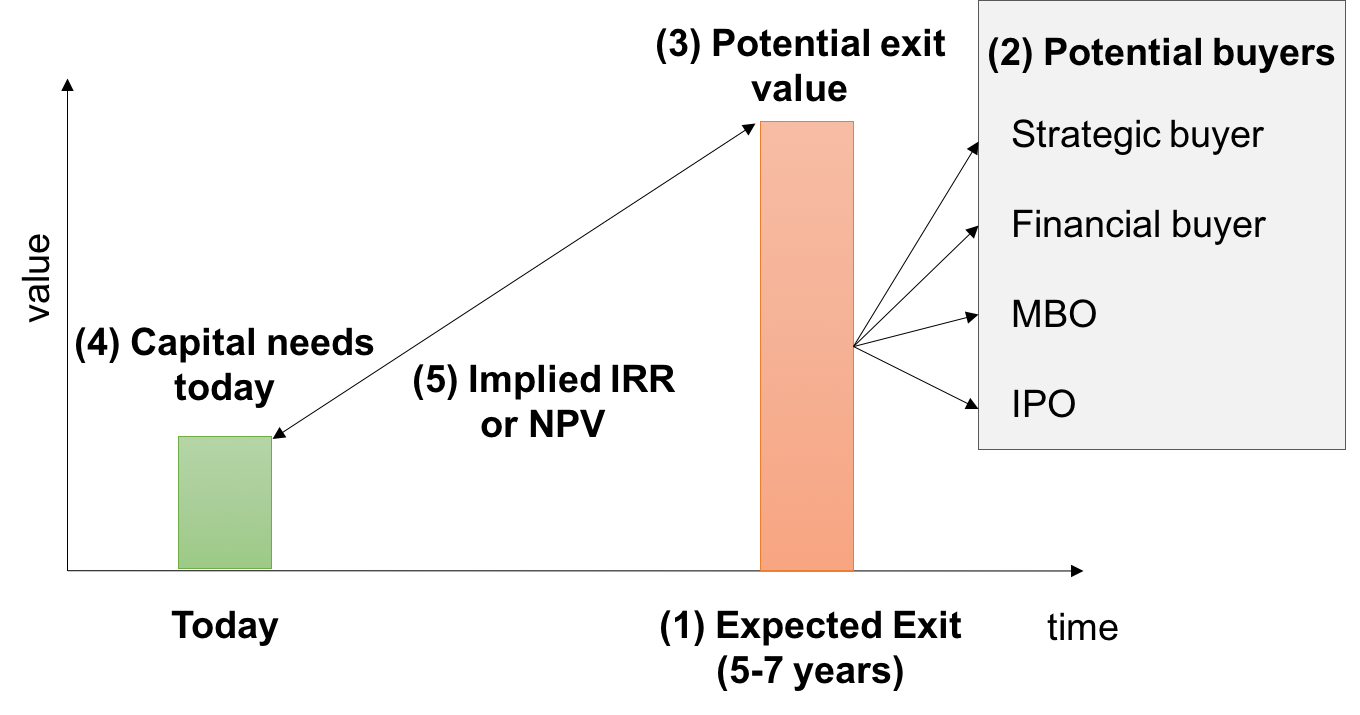

The VC Approach factually conducts a reverse calculation by assessing the following questions:

- When can we expect to be able to exit from the investment (sell the shares), given the current business plan?

- Who might be potential buyers of the company at the time of the exit (financial, strategic, management, IPO)?

- What is the expected sales price at the time of the exit?

- How much capital is needed today (and in the future)?

- Which return (IRR) or net present value (NPV) does this imply for the firm?

Put differently, the VC approach focuses on the trade-off between capital needs today and the expected exit value in the future. It generally ignores the cash flows in between (between the capital investment today and the expected future exit time), simply because startup firms generally do not pay any dividends or other distributions to their investors during the first few years. Instead, they require all their cash (and more) to finance the operating business as well as the ambitious growth plan.

The following graph summarizes the main steps of the VC approach, as outlined above.

From the point of view of the valuation technique (steps 3 to 5), the VC approach does not pose any additional challenge. To determine the exit value, the considerations we made about continuing value in the previous course section apply. In principle, the VC approach does not specify how to estimate the potential exit value (liquidation, exit multiple, permanent growth model, etc.). In reality, however, VCs almost exclusively focus on exit multiples and then discount the potential exit value (3) with their specific hurdle rate.

The following example illustrates this procedure. Suppose we have a startup company with the following characteristics:

- Capital needs: The firm wants to raise 6.7 million today.

- Exit: The business plan implies that exit could be possible after 5 years.

- Potential buyers: A trade sale to a strategic buyer (e.g., customer, supplier, competitor) is the most likely exit route in 5 years.

- Valuation multiple: We assume that the Enterprise Value to EBITDA (EV/EBITDA) ratio properly captures the valuation of such transactions. Recent comparable transactions took place at an EV/EBITDA ratio of 6.

- Financial forecast at the time of exit: At the time of exit in 5 years, the business plan forecasts an EBITDA of 30 million for our firm.

- Hurdle Rate: The VC requires an annual rate of return of 40% for such investments.

Based on this information, we can now conduct the valuation of the company using the VC approach. The expected exit value in 5 years is:

Exit Value5 = EBITDA multiple × forecasted EBITDA5 = 6 × 30 = 180 million.

The present value of this exit value is:

PV(Exit Value5) = \( \frac{\text{Exit Value}_5}{(1+\text{Hurdle rate})^5} = \frac{180}{1.4^5} \) = 33.5 million.

Consequently, the assumptions imply that the firm has a value of 33.5 million today. Since it only requires capital of 6.7 million, the firm, in principle, appears to be a very attractive investment target.

These are the basic valuation steps involved in the VC approach. Clearly, however, the analyst's job is not done yet. By now, we have concluded that the firm, in principle, is an attractive investment target. The logical next step will be to determine what the actual structure of the deal will or should be. For example, we have to figure out which ownership stake (fraction of the firm's capital) the VC will require and how the dilutive effects of future potential rounds of financing could affect these considerations. The details of this analysis will be the topic of the next course section.

Before looking into these imporant considerations, let us quickly (re)visit some implementation issues of exit multiples.