Reading: Introduction to Firm Valuation

This first chapter gives a brief introduction to the valuation journey ahead of us.

2. Introductory Example and Module Outline

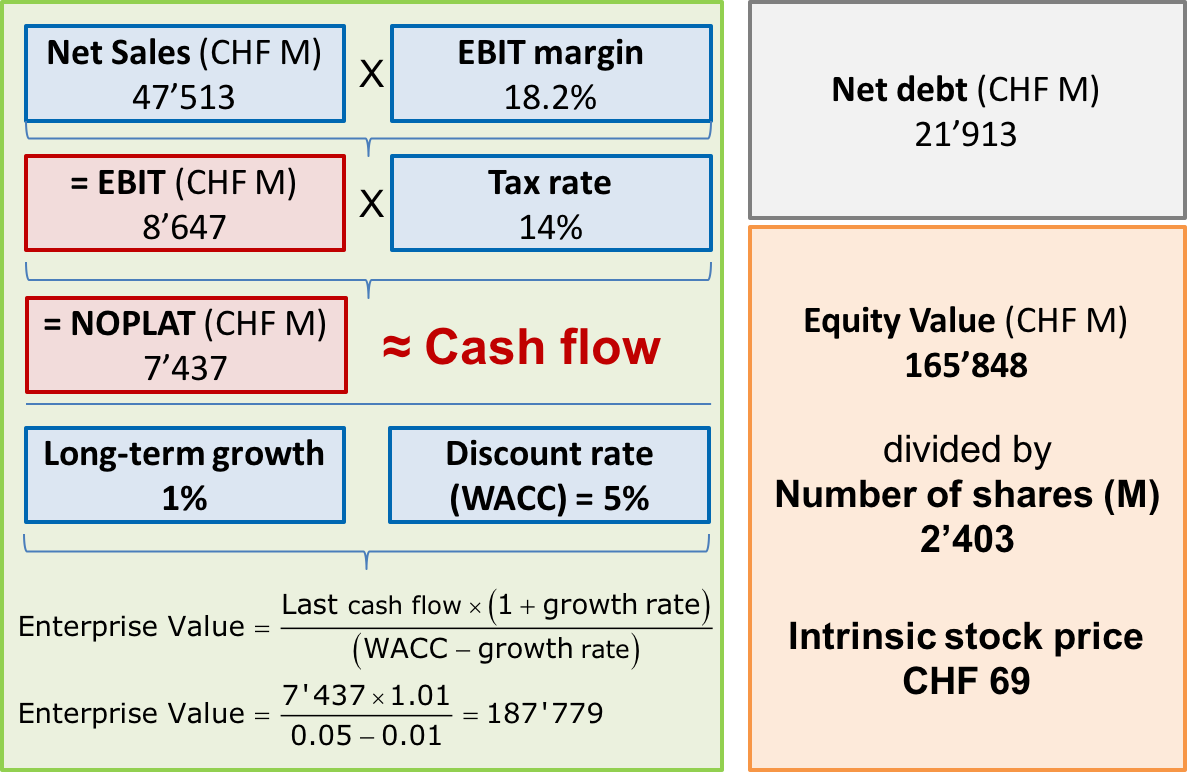

To see how we can obtain a rough estimate of the value of a company (as well as its stock price), consider the following real-life example: Suppose we want to value the Swiss pharmaceutical firm Novartis in November 2016. The previous chapter has shown that we need to estimate the firm's future cash flows as well as its cost of capital to complete this task.

- Cash flows: Let's assume that the firm has generated a cash flow of roughly 7.4 billion in the previous year. This cash flow estimate is based on the firm's actual sales (47.5 billion), profit margins (18.2%), and tax rate (14%). Let's also assume that market participants expect this cash flow to grow by 1% per year forever.

- Cost of capital: Let's assume that the relevant discount rate is 5%.

With this information at hand, we can estimate Novartis' enterprise value using the model of a growing perpetuity. The result of this procedure is shown on the left side of the picture below. According to our estimates, the overall value of the projected cash flow stream is roughly CHF 188 billion:

The 188 billion is the so-called enterprise value. It represents the amount of value the firm is expected to generate by managing its assets in place and future growth opportunities.

However, not all of this value belongs to the shareholders. As it turns out, the firm has interest-bearing financial liabilities with a total value of approximately CHF 22 billion (upper-right part of the above graph). Net of these liabilities, the remaining value that goes to the shareholders is, therefore, roughly CHF 166 billion. This is the so-called equity value.

As the firm's annual report reveals, the total number of shares outstanding is roughly 2.4 billion. Therefore, the equity value per share outstanding is approximately CHF 69. This is our estimate of the firm's stock price. As it turns out, Novartis was trading at exactly this price in November 2016.

The logical next steps

The main challenge we face when implementing such valuation approaches is that the relevant cash flows and discount rates first have to be estimated. Unfortunately, in many instances, it is a bit more complicated than in the example above.

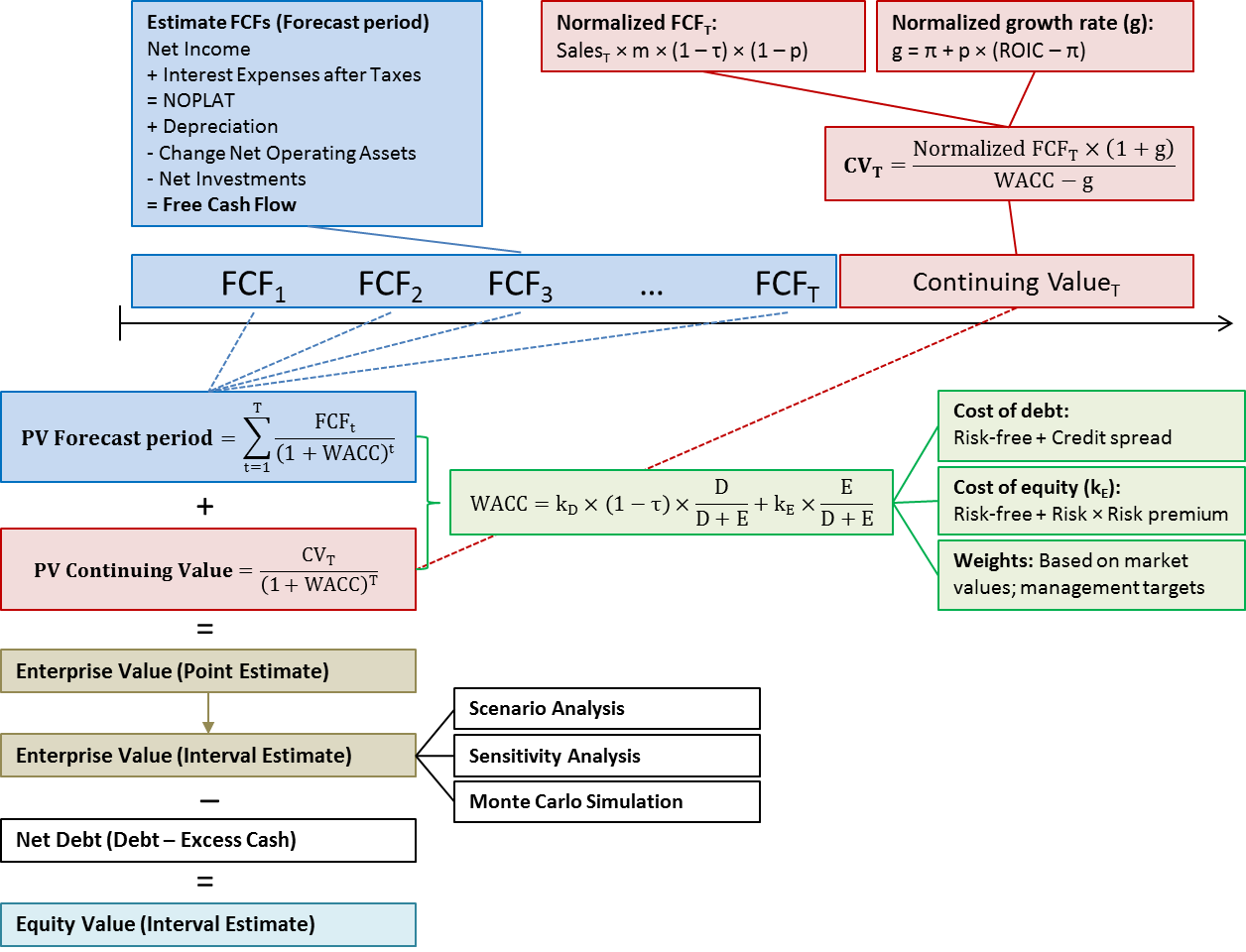

This course provides a step-by-step guide for firm valuation using the discounted cash flow (DCF) approach. The following graph summarizes the main logic of the journey ahead. For the time being, don't worry about the equations in the graph --- they will all be discussed in detail later on.

The module proceeds as follows:

- The first major step is the estimation of cash flows. This is the topic of the two separate modules: Financial Analysis for Managers and Financial Planning for Managers.

- The second major step deals with the estimation of the firm's cost of capital (discount rate) and the question of how to bring cash flows and discount rates together to value a company. This is the topic of the separate module Cost of Capital and Valuation.

- Having learned these basic principles, we then turn to one of the major challenges in firm valuation: For how many years shall we project our cash flows and what happens with the firm thereafter? The estimation of the so-called Continuing Value is the topic of the separate module Continuing Value.

- As we will see, every valuation exercise is the result of a set of assumptions. It is therefore important to understand how sensitive our valuation is to wrong assumptions. This is the topic of the section Coping with Measurement Error.

- The last section then briefly summarizes the whole valuation journey and shows how to get from enterprise value to equity value.

Intrinsic and Relative Valuation

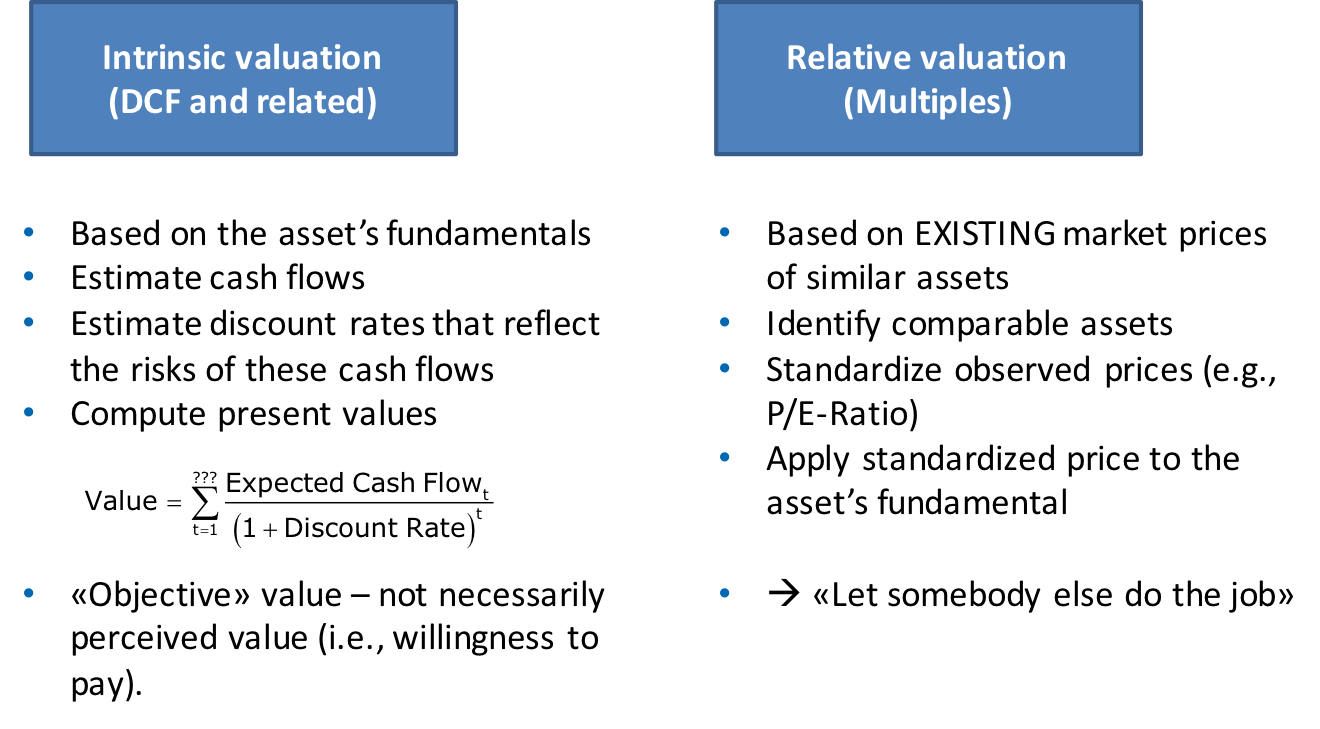

The DCF approach is what the market uses to value firms and other financial assets. Still, the question is whether it is always necessary to do all the work that is associated with the individual steps outlined above or whether there is not an easier way to estimate values. This is exactly the idea behind relative valuation: Instead of deriving financial values based on a detailed model of the financial future of the firm (the so-called intrinsic valuation), relative valuation uses existing market valuations of other firms and applies them to the firm in questions.

Let us illustrate relative valuation with the Novartis example from above. There, we have seen that the market value of the firm, the so-called Enterprise Value was approximately CHF 188 billion. Now suppose we want to value another pharmaceutical company with a business model that is comparable to the one of Novartis. Let's call this firm Pharmartis. How can the valuation of Novartis help us do the job?

- Unless Pharmartis is identical to Novartis in each and every possible dimension, the absolute value of Novartis alone, CHF 188 billion, does not give us too much information about the potential value of Pharmartis. For example, Novartis could be much larger than Pharmartis. Consequently, also its value should be larger.

- The idea behind relative valuation is to make valuations comparabel across companies. What does Novartis' valuation of CHF 188 billion actually mean? Put differently, what do investors get in return for investing in the company?

- To answer these questions, the approach expresses market valuations in relation to some easily observable fundamental value driver. In the above example, such a value driver could be the firm's operating profit (EBIT). Arguably, how valuable a firm is correlates with operating profitability. In the case of Novartis, EBIT was 8.647 billion.

- The result is the so-called valuation multiple: Novartis' enterprise value is 21.74 times its EBIT. Put differently, the firm's enterprise-value-to-EBIT multiple is 21.74:

EV-to-EBIT (Novartis) = \( \frac{EV}{EBIT}= \frac{188}{8.647} \) = 21.74.

- In words, the number implies that the market is willing to pay a value of CHF 21.64 for each CHF of EBIT.

- We can now use this multiple to assess the value of Pharmartis. Suppose Pharmartis' EBIT is 100 million. If we assume the same valuation multiple as for Novartis, then Phamartis' enterprise value should also be 21.74 times its EBIT, namely 2.174 billion:

EV Pharmartis = EBIT (Pharmartis) × EV-to-EBIT (Novartis) = 0.1 × 21.74 = 2.174 billion.

This is, in brief, the basic logic behind relative valuation: Use an existing (DCF-based) valuation of a comparable firm (188 billion in the case of Novartis), normalize this valuation with an easily observable value driver (EBIT of 8.647 billion), and apply the resulting valuation multiple (EV-to-EBIT ratio of 21.74) to the value driver of the firm you want to value (0.1 billion in the case of Pharmartis). The third module of the course (Relative Valuation) will discuss this valuation approach in all detail.

To conclude, the figure below summarizes the main logic behind DCF valuation and relative valuation.