Reading: Dividends vs. Share Repurchases

3. Number of Shares and Earnings per Share (EPS)

Dividends and buybacks both return money to shareholders, but they do so in different ways:

- Dividends trigger a cash consideration to all shareholders and thereby leave the number of shares outstanding unaffected.

- Buybacks, in contrast, lead to a reduction in the number of shares outstanding.

As we have seen before, this difference in the payout mechanism is, in principle, irrelevant for the valuation of the firm. In reality, however, it is often highly relevant. We therefore need to know why it is relevant and whether that relevance is justified.

While buybacks reduce the number of shares outstanding, they often leave the firm's earnings unaffected. The reason is that the firm uses excess cash (or additional debt) for the buyback, which usually only has a marginal impact on earnings. Therefore, as earnings remain the same and the number of shares drops, the firm's earnings per share (EPS) increase because of the buyback: the same earnings are distributed among fewer shareholders.

This is relevant because many managers, analysts, and market participants believe that there is a mechanical relation between earnings per share and stock price, which is, in fact, one of the greatest misconception in the profession.

The source of that believe is the Price-Earnings (P/E) ratio, the most popular valuation multiple among financial analysts (for a detailed discussion of relative valuation, see the module Relative Valuation (Multiples), and in particular the section on the P/E-Ratio):

- To estimate the fair stock price of the company, analysts compute the P/E-ratio of a set of comparable companies and then multiply that ratio with the firm's earnings per share (EPS).

- As the buyback program increases EPS, the valuation multiple is applied to a larger earnings base, which is why the theoretical stock price goes up.

Example:

Consider a firm that generates a net income of $1 million and has 1 million shares outstanding. The firm's EPS are therefore 1:

\( EPS = \frac{\text{Net income}}{\text{Number of shares}} = \frac{1'000'000}{1'000'000} = 1.00 \)

Let us assume that comparable firms trade at a P/E-ratio of 20. Consequently, the firm's theoretical stock price is $20 and the market value of equity is $20 million:

Theoretical stock price = Comparable P/E-ratio × EPS = 20 × 1 = 20.

Equity market value = Theoretical stock price × shares outstanding = 20 × 1'000'000 = 20 million.

Now the firm launches a buyback program for 400'000 shares. Consequently, at the end of the program, there will be 600'000 shares outstanding. Assuming the firm's net income does not change, EPS increase to 1.667:

\( EPS^* = \frac{\text{Net income}^*}{\text{Number of shares}^*} = \frac{1'000'000}{600'000} = 1.667 \)

At a comparables' P/E-ratio of 20, the theoretical stock price increases to 33.33 and the market value of equity remains at 20 million:

Theoretical stock price* = Comparable P/E-ratio × EPS* = 20 × 1.667 = 33.33.

Equity market value* = Theoretical stock price* × Number of shares* = 33.33 × 600'000 = 20 million.

A smaller number of shareholder shares the same earnings base, so the value per share goes up. What is WRONG with this logic?

This logic is fundamentally wrong because it ignores the fact that the firm pays out cash to repurchase shares. The cash payout reduces the value of the firm's equity!

To see this, we can go back to the previous example:

- Let's assume that the initial valuation is correct and that the firm does indeed trade at a stock price of $20 for a total equity value of $20 million.

- For simplicity, let us also assume that the firm is fully equity-financed and that it currently has $8 million of excess cash available.

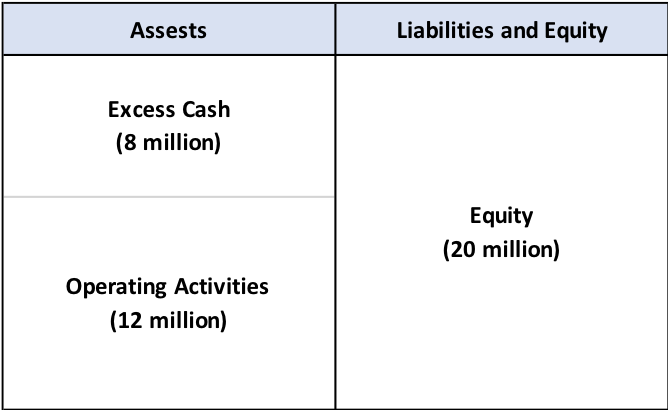

- So the firm's current balance sheet at market values looks as follows:

Now the firm executes the repurchase program as outlined above:

- It repurchases 400'000 shares. Let us assume the transaction occurs in the open market at the prevailing stock price of $20.

- To repurchase the shares, the firm consequently uses up the excess cash of 8 million (= 20 × 400'000).

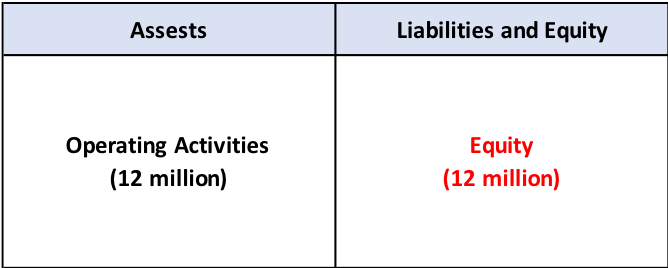

- At the end of the buyback program, 400'000 shares will be gone, but so will be the firm's excess cash of 8 million! Consequently, the sole remaining asset will be the firm's operating activities that are valued at $12 million.

- After the buyback program, the balance sheet at market values will therefore present itself as follows.

- The cash payout of $8 million reduces the value of the firm's equity from $20 to $12 million.

- At the same time, the number of shares drops from 1 million to 600'000.

- Consequently, after the repurchase, the fair stock price will be:

\( \text{Stock price} = \frac{\text{Equity market value}^*}{\text{Number of shares}^*} = \frac{12'000'000}{600'000} = 20. \)

- This is the same stock price as before the announcement.

Intuitively, this result should make sense: If the firm pays the fair stock price to repurchase shares, it does not add or destroy any value. This is also the same conclusion as we have derived when discussing the basic mechanics of buybacks.

This is a very important takeaway: The earnings accretion that share buybacks generally bring about do not mechanically increase stock prices. That would, in fact, be too good to be true.

Yet it is a reality that many analysts focus on EPS and that many managers are willing to take great pains to make sure that they do not miss EPS targets or expectations.

In this context, the findings of Almeida, Fos, and Kronlund (2016) might not come as a surprise: The authors show that firmst that are about to miss their EPS targets are significantly more likely to announce an EPS-increasing share repurchase program. Moreover, their evidence suggests that firms who engage in this practice are willing to trade off investments and employment to meet analyst forecasts.