Reading: Implementing Real Option Valuation

3. Case Applications

3.2. Option to Expand

By commiting to an initial investment, firms often get access to potential valuable projects in the future. These options to expand are present in many industries. Here are some examples:

- Film industry: If a TV series is a great success (e.g., Games of Thrones, House of Cards, The Big Bang Theory, etc.) the owners of the rights can produce additional seasons. Otherwise, they stop after a few episodes or the first season (e.g., The Hasselhoffs, Breaking Boston).

- Technology: Apple is a great example of how to cultivate valuable options to expand. With their unique design, operating system, and marketing approach, they expanded from computers to notebooks, smartphones, tablets, TV, etc.

- Restaurants: Many big restaurant chains started out small. McDonald's for example, started with a single restaurant in 1940 in San Bernardino, California, and sold its first franchise 15 years later.

Even if the first project has a negative NPV, the option to expand into future projects may turn that number into a positive value. Such options are often called "strategic projects." On a stand-alone basis, they do not make much sense. In the bigger context of the firm's strategy, however, they appear valuable. Clearly, arguing with options to expand can also be a bit dangerous because it is sometimes used as an excuse for bad projects.

Example (from Damodaran, p. 228)

Suppose Ambev wants to introduce soft drinks on the U.S. market. As usual in the retail business, it starts with pilot projects in representative areas such as Peoria (IL). We have the following information:

- The cost of launching the limited introduction is 500 million.

- The present value of the associated future free cash flows is 400 million.

- Consequently, the NPV of the limited introduction is -100 million [= -500 + 400].

- However, if the initial introduction works, Ambev could target the whole market with an additional investment of 1 billion at any time over the next 5 years.

- The present value of the expected free cash flows from this expansion is 750 million, according to a DCF valuation.

- The simulation of various DCF scenarios also implies that the volatility of the value changes is about 35%.

- The risk-free rate of return is 5% (discrete compounding).

Should Ambev proceed with the limited introduction?

The project "soft drinks" consists of two sub-projects: Limited introduction and market expansion. On a stand-alone basis, the limited introduction has a NPV of -100 million, as shown above. With the limited introduction, however, the firm gets access to an option to expand on the whole market. The overall value of the project therefore is:

Project value soft drinks = NPV limited introduction + Value of option to expand.

We therefore have to value the option to expand, using the parameters summarized above. According to our Black-Scholes-Merton valuation file, the resulting option value is 217 million:

Consequently, the overall value of the project is positive:

Project value soft drinks = NPV limited introduction + Value of option to expand = -100 + 217 = 117 million.

The numbers imply that the firm should proceed with the limited introduction of the soft drinks.

How real is this real option?

1. Is there a real option embedded?

- The answer would seem to be yes.

- There is an underlying asset - the nationwide expansion of the soft drink line; the firm has the right to exploit this investment opportunity; and the relevant contingencies are also "clear:" expand if if S > X.

2. Is there exclusivity?

- Again, this question is a bit trickier and we do not have sufficient information for a definitive answer. Options to expand could have very strong exclusivity (for example if the firm is granted a nation wide exclusive license by the government), weaker exclusivity (brand name, market knowledge), to weakest exclusivity (first mover). In the specific case, we are most likely dealing with an opportunity rather than an option.

- Note that under different circumstances, the "exclusivity" granted by the initial project could even be negative. Many startups, for example, exhaust all their resources to bring a product to market success. A large incumbent player could simply wait on the sideline and see how the project evolves. If the project looks promising, the incumbent player can "simply" mimick the startup and push the product on a scale that is unaffordable by the small player.

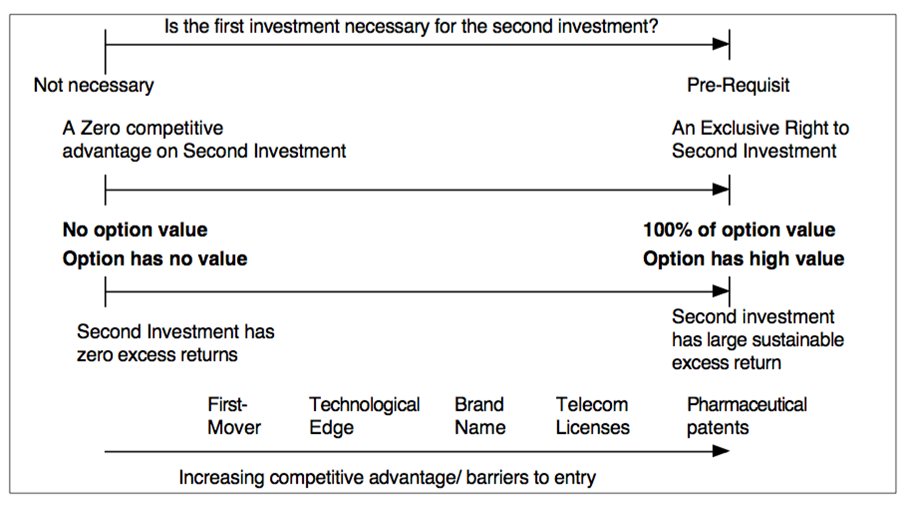

- In the context of expansion options, Damodaran proposes the following three dimensions to assess whether there is exclusivity:

- Is the first investment necessary for the second investment? For potential competitors of Ambev, that would not seem to be the case. If they see that the product works, they can direcly attack Ambev on the nation-wide market.

- Do we have a competitive advantage on the second investment? In the case of a licence or a pharmaceutical patent, the holder has an exclusive right to the second investment (production). Exclusivity could also come from specific learning effects from the first investment (e.g., how the technology works, etc.) In the case of Ambev, exclusivity to the second investment seems limited.

- Does the second investment add value? Is it a commodity (zero excess return) or can we expect to earn a large sustainable excess return (e.g., in the case of pharmaceutical patents).

- The following graph from Damodaran summarizes the three dimensions and illustrate how competitive advantage/entry barriers increase as a function of these dimensions.

3. Can we use option pricing models?

- Neither the underlying asset (soft drings) nor the option (expand production) are traded. So we will need our own valuation to assess S and σ, and possibly also X.

- However, there are a few large soft drink producers (e.g., Coca Cola, Pepsi, etc.) that we could use as comparable firms to benchmark our estimates for the value of the underlying asset as well as the volatiliy.

In sum, there is a real option embedded in the project but it is not clear how valuable it is, given that exclusivity might be limited. Moreover, there are a few challenges to estimate the valuation parameters. Consequently, the result of the valuation will be noisy and we risk overestimating the value of the project as a whole.